The Way It Is/ Discussing cockpit protection & IndyCar safetyby Gordon Kirby |

In the aftermath of Justin Wilson's death there's been lots of talk about introducing cockpit canopies to Indy cars or open cockpit cars in general. But this is an idea who's time has passed. The FIA has taken a serious look at added cockpit protection in Formula 1 and after lengthy consideration they've decided that canopies are not the way to go.

In the aftermath of Justin Wilson's death there's been lots of talk about introducing cockpit canopies to Indy cars or open cockpit cars in general. But this is an idea who's time has passed. The FIA has taken a serious look at added cockpit protection in Formula 1 and after lengthy consideration they've decided that canopies are not the way to go.

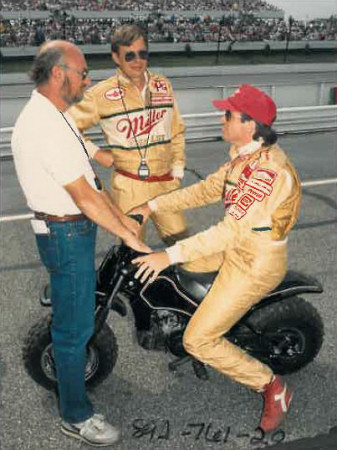

The concept of enclosing a Formula 1 car's cockpit was always opposed by the late Dr. Sid Watkins who was F1's medical director for almost thirty years. Watkins' primary objection was that any such contraption would make it more difficult and time consuming to extricate an injured driver and I have no doubts that Watkins was right. There are plenty of other concerns about enclosing the cockpit of an open-wheel race car. It would surely get very hot inside, requiring plenty of ventilation and air conditioning, which might prove bulky and complicated. In all likelihood most drivers would also struggle with claustrophobia because the space inside would be much smaller than a Le Mans prototype, GT car or NASCAR car. Many years ago Stirling Moss once tested a Vanwall F1 car fitted with a cockpit canopy and he found the car insufferably claustrophobic. Much the same was said about the Sumar streamliner that ran at Indianapolis in the mid-fifties.  © LAT USA And too, enclosing the cockpit would substantially change the air flow over and around the car. Developing the best aero package for an enclosed cockpit probably would cost millions in wind tunnel money. It might also open up some unintended consequences and would likely produce another expensively arcane aerodynamic game. A few weeks ago Charlie Whiting commented on the FIA's search for improved cockpit safety in F1. "We've been working on this for a few years and came up with a number of solutions to test, some more successfully than others," Whiting said. "We had the fighter jet cockpit approach, but the downsides to that significantly outweighed the upsides. "We also came up with some fairly ugly looking roll structures in front of the drivers, but they can't drive with it as they can't see through it. So it's been really, really hard to come up with something that is going to do it. "But we have two other solutions on the table, with the first something from Mercedes. It doesn't cover the driver. You can still take the driver out, which is one of the most important things, and it's a hoop above the driver's head and forward of it, but with one central stay. "We are also looking at another device which is blades of varying heights which will be set on top of the chassis and in front of the driver at angles which will render them nearly invisible to him. "We have put in a huge amount of time, effort and research into this project, which has not been easy, in fact it's bloody hard. But I can definitely see the day when this will happen. One day there will be something that will decrease a driver's risk of injury. "Whether it will be as good at protecting a driver from an object coming towards him as a fighter jet cockpit, I doubt that, but it will offer him protection. We have to persevere. We must make something, even if it's not 100 per cent in terms of protecting the driver under all circumstances. But if it improves the situation it has to be good. There must be a way."  © Racemaker/Dennis Torres Bennett with Kirby and Danny Sullivan, 1988 To take it another step further and lose any view of the driver hidden inside a tightly-enclosed cockpit might seem to many to be another inevitable step on the road to driverless race cars and the complete absence of any human element to the sport. Bearing these thoughts in mind I asked former Indy car designers Nigel Bennett and Bruce Ashmore for their views on this subject. Here's what they had to say, starting with Bennett who designed a long line of superb Lola and Penske Indy cars through the eighties and nineties. "Without having done any work on the subject," Bennett noted, "some reasonable solutions do seem possible. Keeping the driver's head visible does seem important in this form of racing. Being able to get the driver out if he is incapacitated, is obviously important. "First, a few thoughts about bubble canopies. Could they withstand the impact of an object weighing several kgs impacting at around 200mph? I think there is a very anti view from drivers in F1 to enclosed canopies. "How do you deal with dirt, rubber and oil on ovals? And rain on road tracks? Screen wipers? A friend of mine in the U.K is developing ultrasound wipers for screens which will eventually do away with mechanical wipers. They are already in use for clearing machine tool windows of cutting fluid spray. "I don't know if IndyCar suspension arms are of steel or carbon these days? Steel would be less liable to fracture in impacts. Minimal cross section dimensions may be needed. "As far as added protection for the driver, I would have thought that if three struts inclined, but vertical in the fore and aft plane, were in front of the driver, they could deflect foreign objects above and over the drivers' head. From the driver's eye view they would have to be slim, but if they were placed about where a windscreen would be they should not impede the drivers view too badly. "In side view these struts would be at say 45 degrees inclination, and probably no more than 15 cms high. Their fore and aft section would have to be quite broad and their anchorage to the chassis structure considerable, to withstand impact from a substantial object such as caused the damage to Justin Wilson. "Cars often have a pitot tube mount placed in front of the driver which don't impede his view. If these were structural and designed to deflect foreign objects they would help to do what is required. My suggestion is three such pillars should be a feasible proposition." Bruce Ashmore was Lola's Indy car designer from 1988-'94, then worked in the USA as Reynard's chief development engineer until the company closed its doors. Today, Ashmore runs his own Indianapolis-based engineering consulting business.  © Racemaker/Swope Ashmore with Michael Andretti, 1989 "The impact problems I believe could be overcome with design and specification of materials but all the other problems Nigel is listing are hard to overcome. Series like NASCAR and Sports car racing have spent years working out those problems and of course NASCAR doesn't race in the rain. "Now if you look at the video of Justin's accident, when the nose box bounced off of Justin's head and chassis it was launched way into the air and very nearly hit another competitor. The nose could have easily hit Justin or anyone else from quite a height. "The fin idea that Charlie and Nigel talk about might work from a forward impact point of view and, if strong enough, might have saved Justin. But they would need to be incredibly strong to stave off a bouncing object like a nosecone and what about a wheel assembly? So my thoughts are more towards modifying the car construction design so that even more effort is applied to keeping the cars in one piece after initial impact. "It does look like a nose bounced along the track and caused the problem. So why does IndyCar have a spec car with a quick release nose system? To speed up a nose change during a pit stop? These kind of features are kind of alright when you have competition between manufacturers and only then if one manufacturer has it and others don't. But when all the cars are the same, is it really necessary? "If you go back a few years the Indy car chassis construction had several large diameter bolts holding the noses onto the chassis. This was because we wanted the nose to stay mounted to the chassis after initial impact and continue to be mounted after several more impacts with the wall during a crash. "Yes, this impeded a quick nose change if the driver knocked off a front wing during competition, but we felt the long term safety of the complete system, both for fans and drivers, was more important if we kept the driver safety cell in one piece. This includes the nose cone attached to the chassis. "Another point to note is that it could have easily been a rear wheel pod that came off another car and hit a driver's head. There were a few of those bouncing along the track after the crash. These seem just as likely to be able to cause problems as they seem to fall off regularly after initial wrecks.  © LAT USA "So I think we are left with the design challenge of keeping the car in one piece after impact," Ashmore concluded. "I believe the use of some steel structures in the car construction would be beneficial. Some steel tubular frames and steel tubular cross braces with cables, if designed correctly, would keep these parts attached because the steel tubes would bend and the cables would act as ties and keep the carbon crushable box structures attached after multiple impacts. "The wishbones are made of steel on an Indy car but they are still very flimsy in design, something left over from the competition days of multiple chassis when we had a war between chassis manufacturers and we were striving for lighter and lighter structures. More steel could be used elsewhere on the car design to keep the cars in one piece after impact in a crash situation. Perhaps also more rope tethers onto bodywork pieces would be beneficial." Ashmore raises some salient points about IndyCar needing to improve the way Dallara attaches the noses of of its Indy cars and to the larger picture of the rear wheel pods and other body parts that we've seen bouncing down the track too many times this year amid accidents on ovals, road courses and street circuits. Many people like Bennett and Ashmore predicted that this year's aero kits would result in the cars running closer together than ever and the prediction has come true on all types of tracks. In this environment multi-car accidents are inevitable and potentially ruinous on big ovals in particular. When the aero kits were first rolled out many people also predicted that many accidents would result with lots of debris flying around from the numerous aero kit bodywork pieces. Sure enough, they were right again. To move forward IndyCar needs not only a more aesthetically pleasing car but also one with more cohesive, crash-resistant bodywork. In the wake of Derrick Walker's departure IndyCar faces as many technical and commercial challenges as ever, maybe more. Some brilliant, practical thinking is desperately required in company with the need to create consensus, offer inspired leadership and provide first class execution. And of course, IndyCar also needs to develop a stable, consistent schedule which is an entirely separate and equally desperate matter. In all, it's a very tall order. |

|

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright ~ All Rights Reserved |