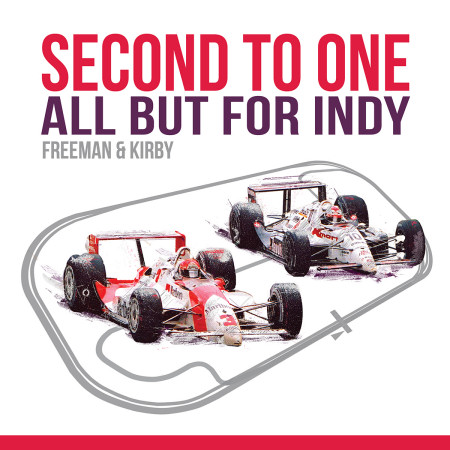

The Way It Is/ The importance of aesthetics & charismaby Gordon Kirby |

One day last week I was proudly showing a copy of 'Second to One' to my neighbor Van Webb. Van runs his family's Harding Hill Farm and among other things he's a two-time New Hampshire Tree Farmer of the Year. He's also a casual race fan who attended three or four CART races at New Hampshire Motor Speedway some twenty years ago and took in a few NASCAR races at the track before the novelty wore off.

One day last week I was proudly showing a copy of 'Second to One' to my neighbor Van Webb. Van runs his family's Harding Hill Farm and among other things he's a two-time New Hampshire Tree Farmer of the Year. He's also a casual race fan who attended three or four CART races at New Hampshire Motor Speedway some twenty years ago and took in a few NASCAR races at the track before the novelty wore off.

Within seconds of starting to flip through 'Second to One' Van's eyes lit up. Grinning widely he pointed to a page of photos of 1972 Eagle Indy cars. "Boy, what beautiful cars!" he exclaimed. As Van continued to flip through the book he stopped to glance at some classic roadsters from the fifties and a selection of Harry Miller's finest cars from the twenties and thirties. He paused to take in a particularly sleek, low slung front wheel drive Miller from the late twenties.  © Racemaker Press Wise words from a casual race fan who is quite accomplished in his own field. I believe they reflect the views of the vast majority of potential IndyCar fans around the world who are turned off by the distinctly unattractive Dallara DW12. I recommend 'Second to One' to anyone for a useful perusal of the history of Indy car racing and the essential roles played by innovation and aesthetics in the sport's popularity over many decades. Like many people who appreciate the sport's great history I continue to believe that if IndyCar is to have any hope of rebuilding its lost fan base and media following it must find a way to produce a more attractive and aesthetically-appealing car as well as inspiring competing car builders. Sadly, only a few months into the game, IndyCar's aero kit experiment appears to have failed. It's been very costly for the teams and hasn't brought any uptick in crowds, TV ratings or overall media interest. Many team owners have criticized the costs of the aero kits while the entire experiment has played into the hands of the biggest, most well-funded teams and could backfire in the worst possible way if Honda decides, as suggested, to pull out. Derrick Walker hoped to use the aero kits as the first step in opening up development of the existing car but Roger Penske said two months ago that there shouldn't be any more rule changes for two or three years. Penske says nobody can afford the technical development that Walker and many fans would like to see. The fact is any development of IndyCar's formula is severely hamstrung by the cost constraints that have occurred as a result of the series tiny media footprint. Another serious problem is that even if the sponsorship and money was available to pay for competition among car builders there's no competition left anywhere in the world for Dallara. Over the past ten or fifteen years the Italian manufacturer has established itself as the world's unrivaled leading production race car manufacturer or spec car builder. Today, Dallara supplies almost every conceivable open-wheel category below Formula 1 with spec cars while the likes of Lola, Reynard, Swift and Penske are no longer in the car-building business. Given the huge investment and technical capabilities required it's extremely unlikely that any other car builder will emerge in the foreseeable future with the infrastructure and financial resources to compete with Dallara. So the dream of IndyCar becoming something different than what it is appears to be no more than a myth. IndyCar is what it is, and thus will it continue.  © Mike Levitt/LAT USA And that's not Dixon's fault. It's a result of the debilitating effects of the failures of CART, ChampCar and the IRL including the destruction of more than 40 races over the past twenty years all of which have led to IndyCar's desperately weak role in the American sports market. Without doubt Indy 500 winner and championship leader Juan Pablo Montoya is IndyCar's biggest star. The Colombian has a much bigger worldwide reputation than any of his competitors because he's a multiple F1 race winner and also made a name for himself in NASCAR. Like it or not, Montoya's years in F1 and NASCAR mean he has much greater name recognition than anyone like Dixon who's spent his entire career in IRL or IndyCar. At dinner one night in Montreal a few weeks ago for the Canadian GP I was intrigued by a conversation with our waiter. He asked if we were in town for the Grand Prix and we said, yes, we were. He said he had become a fan of F1 almost twenty years ago when Jacques Villeneuve won the World Championship with Williams-Renault. He added that he then became a fan of Michael Schumacher as the German won title after title with Ferrari. "Schumacher was a real superstar," our waiter observed. "He was a great driver and a guy who really defined F1. Everyone knew who Michael Schumacher was. "After that, there was Alonso but he never established himself like Schumacher as a multiple champion. He never became the superstar that Schumacher was. Today, there's nobody like Schumacher. I think that's why Formula 1 has been losing popularity around the world." I asked what he thought of Lewis Hamilton. "He's a good driver," he shrugged. "But he's not a superstar like Schumacher. He's a fast young guy but he doesn't have any of Schumacher's charisma." To me, the equation for successful motor racing is simple. It requires attractive, aesthetically-pleasing high-performance cars built by competing manufacturers and driven by charismatic superstars. Any category that doesn't enjoy those critical elements is doomed to mediocrity. |

|

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright ~ All Rights Reserved |