The Way It Is/ Mark Donohue & Porsche's turbo 917 Can-Am carsby Gordon Kirby |

Mark Donohue was the quintessential Penske driver. He was Roger's second full-time hiring after Karl Kainhofer when Penske started his team in 1966 and through Penske Racing's first ten years Donohue drove an incredibly rich stew of cars in Can-Am, USRRC, Trans-Am, long-distance sports cars, NASCAR, Indy car racing and Formula One. But the magnum opus of Donohue's remarkable career were the Porsche 917/10 and 917/30K Can-Am cars of 1972 and '73, the product of Penske's first partnership with Porsche.

Mark Donohue was the quintessential Penske driver. He was Roger's second full-time hiring after Karl Kainhofer when Penske started his team in 1966 and through Penske Racing's first ten years Donohue drove an incredibly rich stew of cars in Can-Am, USRRC, Trans-Am, long-distance sports cars, NASCAR, Indy car racing and Formula One. But the magnum opus of Donohue's remarkable career were the Porsche 917/10 and 917/30K Can-Am cars of 1972 and '73, the product of Penske's first partnership with Porsche.

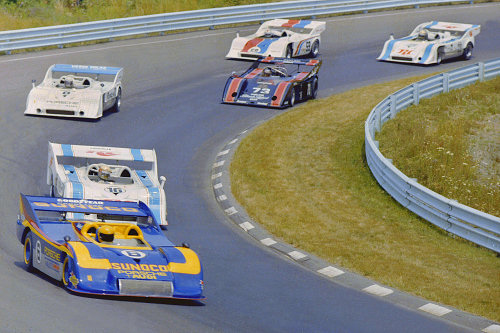

Donohue of course was also Penske's chief engineer who often drove the truck, swept the shop floor and spent many nights sleeping on a bed above the workshop. I doubt that any other driver in the sport's history has worked so many hours or been such a hands-on focal point of any team. Consider that in 1971 Donohue managed and raced cars in six different categories. He ran nine USAC Championship races, Indy included, driving a Lola-Ford, then a McLaren-Offy; swept the Trans-Am championship winning seven races aboard a Penske/AMC Javelin; ran the Daytona 24 hours, Sebring, Le Mans and Glen 6 hours in the team's Ferrari 512M with David Hobbs co-driving; raced the 512M in the Can-Am race at Watkins Glen; did the Questor GP F1/F5000 challenge race aboard a Lola-Chevy; and in September finished third in his F1 debut driving a Penske-prepared McLaren M19 in the Canadian GP.  © Racemaker But in '71 Penske and Donohue found what they believed was a way to challenge McLaren's domination of the Can-Am series when Porsche proposed a deal for Penske to work with them to develop and race a turbocharged Can-Am car for 1972 based on the 917 long-distance sports car. In his classic book 'The Unfair Advantage' Donohue and co-author Paul Van Valkenburgh wrote about the capability Donohue saw at Porsche. "I recognized immediately that it was a miniature Chevrolet Research and Development," Donohue wrote. "We saw that they had everything we could possibly need--dynos, component test machines, tyre testers, chassis shakers, hot rooms, cold rooms, door latch testers, and so on. It was just smaller than GM. They had five racing engineers, instead of five thousand. We were truly impressed. We reckoned all we had to do was put the operation in the proper gear, push it forward, and we would have unlimited success." Donohue spent the winter testing and developing the car working first at Weissach, then in the United States. Helmut Flegl was Porsche's chief engineer on the project and it took a huge amount of work to sort out the prototype's suspension geometry and aerodynamics and the engine's fuel metering system. The 5.0 liter turbocharged flat-12 engine made more than 800 bhp and the first 917/10 was ready for the '72 Can-Am season-opener at Mosport. Two weeks before the Can-Am opener Donohue won the Indy 500 aboard Penske's McLaren M16B and at Mosport he out-qualified the McLaren M20s driven by Revson and Hulme by almost a full second. He then dominated the race until a turbo valve stuck. After a pitstop he rejoined to finish second behind Hulme and ahead of Revson whose engine blew a couple of laps from the end. Round two of that year's Can-Am series was at Road Atlanta and Penske's team went down to Georgia for some pre-race testing. But disaster struck when the rear bodywork broke loose while Donohue was in the fastest section of the track. The 917/10 hit the bank hard, cartwheeled down the road and comprehensively destroyed itself. Donohue was lucky to escape with nothing worse than a broken left leg, but he was out of action for a couple of months. Penske immediately called George Follmer to replace Donohue. Follmer was the 1965 United States Road Racing champion and had driven for Penske in the '67 Can-Am series in a second Lola T70 beside Donohue. He had also won races in Indy cars and the Trans-Am series. Without benefit of any testing Follmer qualified second to Hulme at Road Atlanta and ahead of Revson. In the race he took the lead at the start and won easily after Revson ran into ignition trouble and Hulme crashed spectacularly on the fifth lap while chasing hard after Follmer.  © Racemaker Follmer admits the 917/10 was the most difficult car he had to learn to drive. "I like to refer to it as a steep curve in my educational level," he remarks. "It really was because here was a piece of equipment that worked pretty well and had great potential but it wasn't always the easiest thing to drive. It had its limitations, as every piece of equipment usually does. You work around them and try to fix them. It was extremely challenging from a driver's standpoint because of its characteristics. "For me, it was a very rapid learning curve. You either learned it or you crashed it and they would get somebody else. Anybody who got into it, no matter who he was, or where he came from, would have been on a severe learning curve. Mark was the only one who had any experience with it. "I didn't have a lot of feedback to them because I didn't have any expertise with the car," Follmer adds. "I never tested the car. The only time I got to run it was when we went to a race and you don't have any time to develop at a race. I would say it took me four races before I felt that I could get anywhere near the potential of the car." Follmer struggled at the next Can-Am race at Watkins Glen. He was out-qualified by Hulme and Revson and outpaced by both McLarens in the race until stopping to fix a jammed turbo valve, like Donohue encountered at Mosport. George rejoined to finish a distant fifth while Hulme and Revson scored a one-two sweep for McLaren. "At Watkins Glen we didn't do very well," Follmer says. "A lot of it was because we didn't have Mark's expertise of knowing what the car liked and didn't like. That page was missing from our bible and I didn't have the expertise with the car. We kind of stumbled and bumbled and then we had a problem similar to what had given Mark difficulty in the first race at Mosport. We finished, which was a good thing, because we certainly weren't going to win the race that's for sure." Next came Mid-Ohio where Donohue appeared on crutches to provide set-up and driving advice to Follmer. With Donohue behind him Follmer was able to begin to get the best out of the car. He beat Hulme and Revson to the pole and won the race convincingly despite spinning twice amid some light rain. The weather changed back and forth resulting in Hulme stopping five times to change tires while Penske kept Follmer on the track throughout the race on dry tires. "We got to Mid-Ohio and it started coming to me," Follmer says. "Mark was back to help with the car and that made all the difference in the world. Goodyear also came out with a tire that was built for the car. It was nineteen inches wide and that helped handle all that horsepower. I was getting more familiar with the anticipation of the throttle lag and where you wanted the power and how much power you wanted and how much you could get away with. It was just a matter of experience. "It was a great car," Follmer adds. "It was reliable, it was fast and it had good brakes. It had shortcomings, but they always do."  © Dan Boyd Donohue returned to action for the year's last four races as Penske ran two 917/10s. Donohue beat Follmer to the pole at Brainerd and Edmonton and won at Edmonton after Follmer had to stop to replace a punctured tire. Follmer wrapped-up the Can-Am title by winning the last two races at Laguna Seca and Riverside with Donohue taking second at Laguna and third at Riverside behind Revson's McLaren. "It was good that Mark got back in the cockpit and was able to get back in the groove," Follmer relates. "After a shunt like he had, it takes a little while to readjust and start doing it again. Anybody who tells you otherwise is lying to you. I've been there myself. Getting back in and thinking you can be at the level that you were when you had the mishap, those are two different numbers." For 1973 Penske reverted to running just one car for the fully recovered Donohue. A new car, the 917/30K, was under development for Donohue and Penske to race in '73 while Follmer joined Bobby Rinzler's new team. Rinzler bought two 917/10s for Follmer and paying driver Charlie Kemp but the older cars were no match for the 917/30K. The new car enjoyed a longer wheelbase, much improved aerodynamics and more power--as much as 1,100 bhp--from the latest 5.4 liter engine. "I had run the 917/30 test car at Weissach before it was introduced," Follmer recalls. "I did some laps and tested some stuff and I knew we were in trouble. I knew what was wrong with the 917/10. Mark and I both concurred that the 917/10 needed a longer wheelbase to make it easier to drive in the high-speed corners. The other thing was the aerodynamics were more efficient on the 917/30 because it was a much cleaner car." The 917/30 was substantially quicker on the straightaways. "The 917/10 was about a 200 mph car," Follmer says. "We would get up to 190 plus and it was like it hit a rock. It just wouldn't go any faster. It would go a little faster if you had another mile or two of straightaway. But for our Can-Am racetracks of the day 195-200 mph was about as much as we could get. It just wouldn't go any faster. But the 917/30 jumped the straightaway speeds up fifteen mph because it had much better aerodynamics. "The 917/10 could run with the 917/30 at a track like Laguna Seca. We could run with it, but we probably couldn't beat it. But at fast racetracks like Elkhart or Riverside there was no chance. Mark's straightaway speeds were at least fifteen mph better than ours. He probably had a little more horsepower but the aerodynamics were much better." Indeed, after a slow start, Donohue ran away with the 1973 Can-Am championship, winning the last six races in a row with little or no opposition. Knowing they were out-powered by the turbo Porsches the McLaren team quit the Can-Am prior that year and Donohue's only serious competition came from Follmer and a youthful Jody Scheckter aboard another 917/10 run by Vasek Polak.  © Dan Boyd "Those cars would jump right out of the pit and bite you just as easy as looking at you," Follmer remarks. "They were a very aggressive race car. They had power and they went fast. You had to stay on the wheel." Follmer says without doubt Donohue was the key man in making Porsche's turbo Can-Am cars successful. "I think a lot of credit goes to not only the engineers at Porsche but to Mark Donohue. Having Mark work with them and help them with their ideas was more of a factor than a lot of people give Mark credit for." But Follmer believes Donohue took on too much work and responsibility. "His work ethic was up on a level with 'The Captain'. They were made for each other. Mark was everything to Roger's team. Mark was carrying a heavy load and carried more and more all the time. He was the guy in charge. He got more and more involved and got more and more responsibilities put on him. He was always on the phone. He had a direct line to 'The Captain'. At the end, the load he was carrying was ridiculous. He had to be commended for just being able to get up in the morning." At the end of 1973 the SCCA in their infinite wisdom decided to introduce a fuel consumption formula for the '74 Can-Am with a three mpg limit. Porsche was not amused and cancelled the third year of its contract with Penske. The 917/30K ran its last race at Mid-Ohio in the summer of '74. Penske decided the car could compete with the fuel restrictions on the tight Mid-Ohio circuit and hired Brian Redman to drive because Donohue had temporarily retired. The '74 Can-Am series was dominated by the Shadow team with Jackie Oliver and Follmer driving a pair of Chevy-powered DN4s designed by Tony Southgate. "The Shadow DN4 was probably one of the nicest-driving Can-Am cars ever built," Follmer comments. "I didn't drive the 917/30, of course, but the DN4 was a beautiful car to drive. You could just lean on it and lean on it and lean on it, and it would just keep giving you more." Oliver won the championship from Follmer while Redman and the 917/30K battled with the Shadows at Mid-Ohio before coming home second to Oliver. "The car had just been brought out from storage and probably had very little done to it other than checking for the basic safety elements," Redman says. "It hadn't been tested. I didn't drive the car until the race weekend so it wasn't the ideal way to do it. But so often in racing that's what happens."  © LAT USA "I had driven Vasek Polak's turbo Porsche before so the throttle lag and the power wasn't completely new," Brian recalls. "Its handling was very much better than the 917/10. Because of the throttle lag and the necessity to anticipate the response you couldn't balance either the 917/10 or the 30 with the power in the corner as you do with a normal race car. "But I liked the handling of the 917/30. The car had the ability to oversteer gently with the power off which was fantastic because you could let the oversteer put you in the right direction for the following straight and then turn the power on at the appropriate time. The power of the 917/10 and the 917/30 was phenomenal. Once you got them pointed in a straight line they were unbelievable. At Mid-Ohio, which doesn't have much of a straight, we were doing 180 mph. The brakes were terrific. It had great brakes. It was a great car but effectively it killed the Can-Am." Indeed, that was the end of the road for the Can-Am. The SCCA cancelled the flagging series and replaced it with Formula 5000 in 1975. "I'm sure it's something we'll never ever see again," Follmer remarks. "We drew huge crowds and when people look at the old movies or watch the cars today they look at them in awe. We drew big crowds back in those days. 85,000-90,000 was a normal thing and with no facilities at all. What people went through to stand out there in the sun at Riverside to watch a race was something else. You really had to want to watch that race. It was hot, dusty and dry and the sun at Riverside is not very forgiving. "But the cars were spectacular and the drivers raced different types of cars in different series. They weren't specialists like today's drivers. Whatever the reasons, the Can-Am had tremendous appeal to the fans." Of course, near the end of 1974 Donohue decided to return to racing to drive Penske's new F1 car. And in Austria the following summer he crashed in practice and died two days later, a sad end to one of the most remarkable racing careers the world has seen. "I knew Mark pretty well because we had raced together and been teammates together," Follmer reflects. "We were competitors but by the same token we talked to each other once in a while too. It wasn't a stand-off like it is with a lot of people. I told him at one point, 'Don't go back, and don't go back for Formula One.' I had been there and I know how they treat you. F1 is so political and I said to Mark, 'You don't know the tracks, and they're very political and there's no cooperation.' I said, 'Don't do it.' "But he did it anyhow and I know what drove him. It was the same thing with me. Mark and I came up through the sixties in the era of the Can-Am and Trans-Am and we went to Indy together. We did the Trans-Am and the Can-Am and the Indy 500 and the only carrot that was left for us was Formula One." Mark Donohue may not have made his mark on F1 but he defined Penske Racing and is fondly remembered as one of America's most complete racers. For my part, I will always recall Donohue pushing his 917/30K around Elkhart Lake, turbo spooling up, tires chirping while breaking free under power, as he became the first man to break the two-minute barrier around the USA's finest road circuit, more than three seconds quicker than anyone else that day. It was a truly remarkable sight and one of my fondest memories. *The time's come for my annual holiday season vacation. I'll return to my work in this space on January 12th. Meantime, I hope all of you have a pleasant and refreshing holiday break as we look ahead to the New Year. |

|

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright ~ All Rights Reserved |