The Way It Is/ Finding the elusive right balanceby Gordon Kirby |

Back in 1973 and '74 I had both the pleasure and unhappiness to cover the last two years of the original, unlimited Can-Am series. At the time I was a rookie race reporter for AutoWeek and Autosport in the UK and it was sad to cover the demise of the hoary old Can-Am series over those two years.

Back in 1973 and '74 I had both the pleasure and unhappiness to cover the last two years of the original, unlimited Can-Am series. At the time I was a rookie race reporter for AutoWeek and Autosport in the UK and it was sad to cover the demise of the hoary old Can-Am series over those two years.

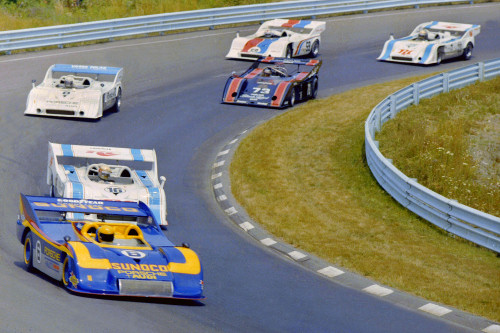

Mark Donohue dominated the '73 Can-Am in Penske's genuinely awesome Porsche 917/30. He was on the pole for all eight races, won six of them and it was a pleasure to witness such a superb racing car in action driven by one of the sport's finest driver/engineers. The SCCA responded to Donohue's domination by putting strict fuel limits on the turbo Porsche for 1974 which resulted in Porsche and Penske pulling the plug on the 917/30 project. Brian Redman raced the car once in '74 at Mid-Ohio and that was the last time we saw a 917/30 driven in anger. Meantime the '74 Can-Am was dominated by a pair of UOP Shadows driven by Jackie Oliver and George Follmer who battled each other on and off the track. Oliver won four races and handily beat Follmer to the championship but the season-closer at Riverside was cancelled after a poor crowd at Elkhart Lake in August. Neither Oliver nor Follmer finished at Elkhart as I watched Scooter Patrick aboard Herb Kaplan's McLaren M20 win what turned out to be the last Can-Am race. The SCCA tried to fill the void with the fast-growing Formula 5000 series which enjoyed a handful of great seasons through the mid-seventies until the SCCA decided to turn F5000 into the 'new era' Can-Am starting in 1977. They hoped to catch the flavor of the original Can-Am but the time had passed and the new cars and drivers lacked the appeal of old. By the mid-eighties the 'new era' Can-Am was dying, passing away in 1986, and that was the end of the SCCA playing any meaningful role in professional motor racing.  © Dan Boyd Of course, it turned out that the SCCA's failures were only a precursor to the ongoing struggles with managing technology and costs which have since roiled across Formula 1, Indy cars, big-time sports car racing and most other forms of racing, even NASCAR. I don't presume to offer any solutions to this deep structural problem within the sport but I do lament the failed attempt to provide some realistic answers to these questions that was a genuine component of CART through its early and middle years. CART's team owners, its technical director Kirk Russell and the drivers, led by Mario Andretti, seriously attacked at least the elements of trying to restrain but not ban new technology. They didn't allow automatic transmissions for example and tried to contain leaps in ground effect improvements by progressively reducing the size or volume of air that could flow through the underwing. A firm decision was made not to go down F1's flat bottom alley in the belief that it would make the cars too pitch sensitive and stiffly sprung. For a few fleeting years through the nineties CART tenuously achieved the elusive goal of maintaining a formula that produced spectacular cars that were a pleasure to drive and race. CART's formula also encouraged thriving competition among car builders and engine manufacturers with Penske, Lola, March and Reynard battling it out on the chassis front and Ilmor/Chevrolet, Ford/Cosworth and then Honda, Mercedes-Benz and Toyota engaging in a fierce engine war. Through its best years CART produced unpredictable racing with multiple winners and a wide mix of different chassis and engine combinations. Even then, F1 tended to be dominated by one or two teams scoring victories with metronomic regularity and as time went on more and more race fans around the world were attracted to Indy car racing as a healthy antidote to F1. Some mistakes were made for sure, most notably the effective banning of All American Racers' Eagle-Chevy 'Boundary Layer Adhesion Technology' car. Many students of the sport suggest this move in the mid-eighties to eliminate the BLAT Eagle-Chevy represented the beginning of the sport's slide into the spec car syndrome and I wouldn't disagree. Still, CART's Indy cars of that era were spectacular, high-performance machines with plenty of horsepower. They were impressive to watch and put on great races. When Ayrton Senna tested a Penske Indy car in 1992 he famously said it was "a human's car" in contrast to the high-tech F1 cars of those days bristling with active suspension systems and fully automatic transmissions.  © Racemaker/Paul Webb My friend and colleague Nigel Roebuck says CART was the world's greatest racing series during that time and many people agree. And as Nigel also says: "The team owners were as guilty as Tony George, were they not, for all the damage that's been done to Indy car racing?" Indeed, they argued vociferously about the engine rules in 2001 as the CART/IRL war blew white hot and the engine manufacturers began to threaten to depart the series for the IRL and the Indy 500. Most team owners preferred ditching CART's long-standing turbo V8 formula in favor of the IRL's much more restrictive engine formula. In fact they voted to do so before Jerry Forsythe dissented and threatened to sue them if they tried to carry out the switch. Of course in the end the team owners sold their shares from Andrew Craig's 1997 stock market flotation and either left the sport or defected to the IRL. It was an unsavory and very disappointing episode in the sport's history and completed the circle of CART's great failed experiment of running the sport through the collective lens of the team owners. Thus we come to where we are today. Are any of the ruling bureaucracies of the sport's major categories--F1, Indy cars, WEC, TUSC, NASCAR, et al.--likely to find the right solutions to a festering nest of technical and commercial problems? Your guess is as good as mine. |

|

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright ~ All Rights Reserved |