The Way It Is/ Celebrating & appreciating Mario Andrettiby Gordon Kirby |

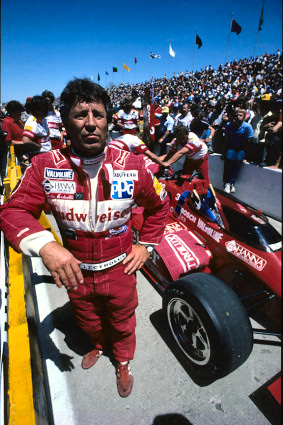

No better man could be grand marshal of next weekend's 40th running of the Toyota Long Beach Grand Prix. Mario Andretti started 19 Long Beach GPs between 1975-'94 and won the race four times, driving an F1 Lotus in 1977 and Newman/Haas Lola Indy cars in 1984, '85 and '87.

No better man could be grand marshal of next weekend's 40th running of the Toyota Long Beach Grand Prix. Mario Andretti started 19 Long Beach GPs between 1975-'94 and won the race four times, driving an F1 Lotus in 1977 and Newman/Haas Lola Indy cars in 1984, '85 and '87.

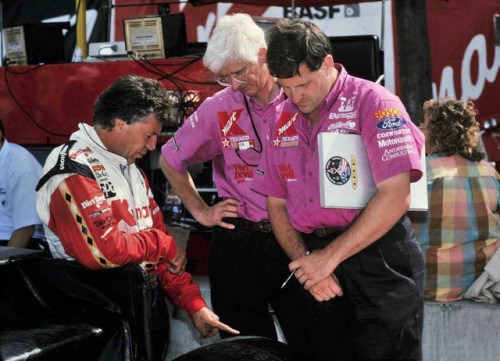

Through those years Mario was known as the King of Long Beach and race founder Chis Pook always said Andretti's victory in 1977 was the key to turning the race from a financial failure into a success. For that and plenty of other reasons many of us are looking forward to celebrating Mario's career on Thursday night at the Road Racing Driver's Club dinner at the downtown Long Beach Hilton hosted by RRDC president Bobby Rahal and enjoying his role as grand marshal of this year's race. Going back to the first Long Beach GP for Formula 5000 cars back in 1975, Andretti was the race's biggest draw. Driving a Vel's Parnelli Jones Lola T332-Chevy he led the first LBGP before suffering a transmission failure. The following year he competed in the first Formula One race at Long Beach driving VPJ's Cosworth-powered F1 car.  © Racemaker/Jim Shane "I found out in the cockpit at the start of the race at Long Beach when Chris Economaki put a microphone in front of my face and said, 'Mario, how's it feel to be in your last Formula One race?' I said, 'What do you think? Am I going to kill myself, or something?' He said, 'Vel Melitich just announced this is his last race.' Neither Parnelli nor Vel had said anything to me." Andretti qualified an unhappy 15th and didn't finish his last race in the Parnelli but the following morning at breakfast at the Hilton he bumped into Colin Chapman. "I was really down," Mario says. "I had this mindset of doing Formula One. I didn't want to do anything else. I felt there was a time in my career and this had to be it. There was no more. If I missed this opportunity, I would have been too old. I was 35 years old and it was already a little late. "So I'm asking myself, 'What do I do?' And here again, as fate would have it, Colin had the worst race he ever had and we're having breakfast in the Queensway Hilton, both of us alone. I was so much in the dumps and I joined Colin and we started talking and we made a deal right then and there."  © Paul Webb Chapman had Swede Gunnar Nilsson and Englishman Bob Evans in his cars at Long Beach, but Evans failed to qualify and Nilsson barely scraped in at the back of the field before crashing on the opening lap when his car's rear suspension broke. "I said I want to do Formula One," Mario recalls about that breakfast meeting with Chapman. "And Colin, said, 'Right. You come on as number one.' I wasn't all that excited because his cars were junk. They hadn't done anything in a few years. He was involved in his new car company and a boat company. The car company went public and he made a pile of money. That's where his interests were at the time. "I said the only way this will work is if you come back full-time to racing. Forget about your car company and the boat company, and come racing, and he agreed. I felt like the horizon had just opened because there was so much potential there." Indeed, Chapman and Andretti's new partnership resulted in Team Lotus developing a series of increasingly effective 'ground effect' cars culminating in Mario winning the 1978 F1 World Championship aboard Chapman's exquisite JPS Lotus 79. Meanwhile, Andretti won at Long Beach in 1977 driving a precursor to the 79 after outbraking Jody Scheckter's Wolf with four laps to go and holding off a late challenge from Niki Lauda's Ferrari. Chris Pook has always said Mario's win that day turned the struggling street race into a success as crowds and media interest blossomed over the following years amid Andretti's run to the 1978 World Championship.  © Paul Webb "Nobody could ever question my desire or my passion for the sport," he says. "But at the same time I had enough pride that I wanted to remember my last year and last days in the sport in a positive way. I looked over my shoulder and looked at some of my compadres who overstayed themselves a little bit. I said I just hope I don't have those memories. That was always my fear and it's real because your career doesn't last forever. "I like to think I accomplished that," Mario adds. "I was still competitive with any of the young guys. I'm sure that some of it was missing, but not a lot, and that's part of my satisfaction in my career. My head is high about my last year. I have great memories. I look at the positives and I think the positives far outweigh the negatives." Brian Lisles was Andretti's engineer through Mario's last five years with Newman/Haas. Lisles says Mario's relentless effort to do a better job continued through his last race and final pitstop. "There were things Mario still did better than Michael, even at the end of his career," Lisles remarked. "When it came down to a pitstop that was really going to make a difference, there was nobody quicker. Nobody would stop the car better and nobody would get out of the pitbox faster than Mario when he really decided he needed to do it. To be honest, that was something Michael was never that good at. Any number of times we used to beat people out of the pits with Mario because he worked hard at it and was very attentive to what was going on when the car was stopped." John Tzouanakis worked for Newman/Haas for more than 30 years and was team manager for much of that time. Tzouanakis says he never saw any real sense of Mario aging. "Mario was still Mario," Tzouanakis observed. "He was getting up there in age but week in and week out we would still have a shot at winning. He would go out to practice and it wouldn't matter if you were on an oval or whatever. He'd maybe do an installation lap and then maybe three or four laps later he'd be going as fast as he was going to go all weekend and it was usually right there with the fast time that people were going to do. It was incredible how he would just get in the thing and go. He would get right up to speed and then start fine-tuning cambers and dampers and whatnot. "He was always in the top five or six and in those days you had quite a few strong cars and teams. Sure, Mario was getting up there in years but compared to who he was racing against you didn't say. 'Here's the old guy competing against all the kids.' He still knew what he wanted and how he wanted to go about things. He didn't slow-down one bit."  © Paul Webb "They had every Goodyear engineer known to man out there and they all said they were disappointed it was all over because they loved to do tire tests with the old man," Hoevel said. "There were times when they'd slip in a set of control tires without telling him and he'd say, 'Ah, you guys are trying to fool me! You can't fool me. I know what you're doing.' There aren't too many people who have that kind of feel." Neil Ressler was Ford's racing boss in those days. Ressler oversaw Ford's technical involvement with the Benetton team in F1 and Newman/Haas in Indy cars. "We were taking instrumentation on those cars in '93 and '94 and I remember Mario would go into the turns and give the steering wheel a flick," Ressler recalls. "The cornering speeds were close to 230 mph and he'd flick the wheel just to see what the car was doing. Honest to God. How he could do that I have no idea. I guess he had good enough car control that he could catch it. "Once we took Mario and Paul Newman on a couple of Ford test drives for Mustangs and Mario picked up some subtleties in the steering that Jackie Stewart had felt. I suppose we believed as part of Jackie's promotional front for Ford that he was the only guy in the universe who could have felt that. But Mario felt it on the first turn. It turned out there were two people in the universe who understood and felt the subtleties that were being talked about." Peter Gibbons was Michael Andretti's engineer in 1992 and engineered Nigel Mansel's car in 1993 and '94 when Mansell was Mario's teammate. "I have the utmost respect for Mario and he was such a part of the team and such a part of the setups," Gibbons said. "His work ethic was just remarkable. Michael hated it when the wind blew at Indianapolis, for example, and dad would say, 'Stay in the garage and I'll sort it out for you.' "We would get to some street courses where perhaps Mario's age and fitness were showing up but it never really dawned on me that his abilities were diminishing or were diminished because he was such a productive part of the equation. Even though maybe he wasn't winning races, behind the scenes he was helping get the setups and was so involved and so intrigued.  © Dan Boyd Gibbons says he's never seen another driver with Mario's relentless work ethic. "He worked so hard at it," Gibbons remarked. "He worked harder than anyone I've ever worked with. Rick Mears was so amazingly naturally talented that he didn't have to work at it. Emerson (Fittipaldi) worked at it, but Mario loved working at it. I think we used fifty-five sets of tires at Indianapolis one year. Nobody was going to tell us that we couldn't have another set because nobody dared tell Mario that. He was just phenomenal. Again, I never thought his abilities diminished. He was a major contributor to our effort until the day he retired. "Mario was the team," Gibbons adds. "His contributions to our setups were incredible. I remember we were testing at Phoenix once and Mario drove in and he said, 'You know, I was driving to work today and I was thinking.' And I said to myself, 'Hmm! I never thought of Mario thinking of this as work.' But this was his profession and he thought about it all the time. "Michael had seen the standard set by Mario and lived with it and he actually matched the standard, but only because he had been exposed to it so much. I think Mike didn't enjoy it like Mario. I never got the impression that Michael enjoyed doing it, but Mario just lived for it." Bruce Ashmore was Lola's chief Indy car designer from 1987-'93. Ashmore says he learned everything he needed to know about how to go testing from Mario. "He is the most influential driver in my career," Ashmore declared. "That's because he loved to test and develop new ideas. He always wanted to try something new. He would be in the car at nine o'clock in the morning and if you had to he would run every hour until six o'clock with the sun in his eyes. Yet he would run every lap the same so that the component you were testing was the difference that made the lap time. From the moment you got to the racetrack in the morning until the moment you went home at night you concentrated on the racing.  © Dan Boyd "The other part of Mario is that when you went to the racetrack he would look at other teams and cars and wonder what they were doing. But he would never say, 'I need that car to win this race.' He would always say, 'How can we make this car beat that car?' He always believed that what I had designed would win the race and the championship, and for a designer that is huge. If you're always looking over your shoulder because you know your driver really wants a March, or a Penske, and not your car, it's hugely deflating. And most drivers are like that." Ashmore says he's never encountered another driver who supported the designer as strongly as Mario. "As a designer you're always criticizing yourself and when you push the car out the door you're never happy with it because you can always think of ways how you could have done it better," Ashmore related. "All you see as a designer is the flaws. So you don't need a driver to point out the flaws and the big thing about Mario was he would never do that. To him, it was always a beautiful thing and he would try everything he could to make that car win the race, and he did a lot of times. "When you went testing with Mario he was always thinking. He was always asking, 'Why do we this?' Or, 'Can we do this, or change that?' I'd always come home from a test with Mario with more questions than I had answers. He was always thinking and pushing." For many reasons, whether it was his work ethic, technical application or racer's heart, or his character and charisma out of the car, Mario Andretti has gone down in history as America's Mr. Motor Racing. At Long Beach next weekend, we will take great pleasure in celebrating his remarkable career and life. |

|

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright ~ All Rights Reserved |