The Way It Is/ Inspired to Designby Gordon Kirby |

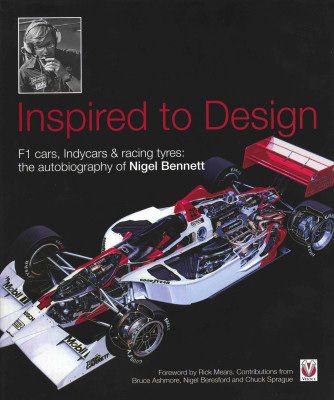

I enjoyed a few snowy days last week reading Nigel Bennett's autobiography 'Inspired to Design'. Bennett cut a wide swath through Formula One and Indy car racing from the seventies through the turn of the century. He was Colin Chapman's development engineer and Mario Andretti's race engineer when Mario won the F1 world championship with the ground-breaking JPS Lotus 79 and went on to design a string of successful Indy cars for Lola and Penske. Between 1984-'97, Bennett's Lola and Penske Indy cars won 79 races, including five Indy 500s, as well as five CART drivers and constructors championships.

I enjoyed a few snowy days last week reading Nigel Bennett's autobiography 'Inspired to Design'. Bennett cut a wide swath through Formula One and Indy car racing from the seventies through the turn of the century. He was Colin Chapman's development engineer and Mario Andretti's race engineer when Mario won the F1 world championship with the ground-breaking JPS Lotus 79 and went on to design a string of successful Indy cars for Lola and Penske. Between 1984-'97, Bennett's Lola and Penske Indy cars won 79 races, including five Indy 500s, as well as five CART drivers and constructors championships.

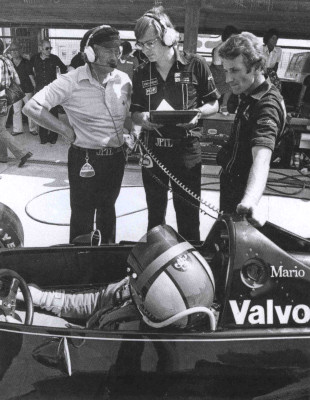

Bennett was born and raised in Derby in the middle of England and studied engineering at London's Auto and Engineering College. During his college days Bennett built and raced his own Austin 750 special, winning a six-hour race at Silverstone in 1965 with a college friend. After graduating in 1966 he got a job with Firestone's fledgling European racing division and worked as a race engineer for Firestone in the Tasman series, F1 and world sports car championship races, quickly gaining valuable experience with top teams like Lotus, Ferrari and Porsche. Bennett worked for Firestone in F1 and world championship sports cars through 1973 until the company decided to close its racing operations. He worked the following year as a tire engineer for Hesketh Racing with James Hunt before joining Lotus in 1975, first as assistant team manager, then as a development and race engineer.  Bennett goes on to write about Chapman's decision to plunge into 'the next step' with the Lotus 80 rather than working on properly developing the 79. Bennett believed Chapman and Lotus had only scratched the surface with the 79 and he wanted to push forward developing the car with which Andretti and Peterson dominated the 1978 F1 season. But Chapman had other ideas and Bennett decided it was time to move on from Lotus after a disastrous 1979 season with the theoretically wingless, fully-skirted type 80. He spent the next few years with Mo Nunn's small Ensign team. Money and resources were tight but the first car was built in only 70 days and looked promising in the year's opening races with Clay Regazzoni driving. But at Long Beach, Regazzoni crashed heavily when the brake pedal broke. The crash brought an end to Regazzoni's F1 career and left him with a broken back and legs, confined to a wheel-chair for the rest of his life. Bennett writes that when the wreckage was examined back in England they discovered the brake pedal had been fabricated without a wrap, as specified on his drawing, to strengthen a weld across the pedal. "Perhaps I should have checked the part myself," Bennett writes, "the brake pedal being such a vital part of a racing car. But the build program had been so rushed, and the team so small that we never had the people or resources to have all the parts properly checked out." Nunn's team finished the year with a variety of drivers and Bennett designed a new car for 1982 driven by talented F1 rookie Roberto Guerrero who was joined in '83 by Johnny Cecotto aboard a second car. The new car and drivers looked good and ran well on occasion, but after three years Bennett told Nunn that without the sponsorship needed to compete at the top level they were fighting an impossible battle.  © Jutta Fausel-Ward Bennett worked with Graham Humphreys to design his first Indy car and the Theodore ran well in testing but Bignotti stuck with his Marches for most of the year. Tom Sneva won the Indy 500 in one of Bignotti's Marches and he and teammate Kevin Cogan drove the Theodore in a few races. At the end of the year Mo Nunn closed his Ensign shop in the UK and went to work as an engineer for Bignotti-Cotter while a new door opened for Bennett when he was hired by Carl Haas and Eric Broadley to design an all-new Lola Indy car for Mario Andretti and Newman/Haas Racing. Newman/Haas was established in 1983 with Andretti as the team's only driver. Lola founder Broadley designed a new car for the '83 season but a huge amount of work was required to make it reliable and competitive. Haas and Andretti decided they wanted a more modern car for 1984 and Bennett was the man they turned to. The resulting Lola T800 brought Andretti his fourth and last Indy car championship in 1984. In designing the '84 Lola, Bennett worked closely with Newman/Haas's engineer Tony Cicale and spent a lot of time uprating various aspects of Lola's design and build process. Andretti won six races and the championship in '84 with Danny Sullivan scoring three more wins in a Lola run by Doug Shierson's team. Over the next few years Lola sold a lot of Indy cars, battling with March for domination of the market, and consistently thrashing Penske's cars. Bennett's 1987 Lola Indy car--the T87/00--was an excellent car. Andretti dominated the Indy 500 that year aboard a T87/00 only to suffer a late-race engine failure, while Bobby Rahal won the CART championship driving a T87/00 for the Truesports team. Meanwhile, Penske Racing was struggling through those years with its PC15 and 16s and Roger Penske asked Bennett to cure his problems and go to work for him to design a winning Penske Indy car. Nor did Bennett disappoint his new employer producing for 1988 the beautiful Ilmor/Chevy-powered PC17 with which Rick Mears won the Indy 500 and Danny Sullivan took the CART title. Sullivan won four races and took nine poles with Bennett working as his race engineer.  © Tony Matthews Bennett writes in great detail about the design and development of his highly successful series of Penskes and about the battle with Lola and later Reynard too. He also covers plenty of ground about building, developing and racing the 'Big Beast' 209 cubic inch rocker-arm Mercedes-Benz turbo V8. The engine was a surprise to everyone else in Indy car racing as Emerson Fittipaldi and Al Unser Jr. dominated the '94 Indy 500 with the engine as Unser won after Fittipaldi crashed. There's also a thorough chapter analyzing what went wrong the following year when Unser and Fittipaldi famously failed to qualify Penske's cars. Bennett's chronicle of the mistakes that were made makes for fascinating reading and emphasizes how difficult it can be to get the Rubrik's Cube that race cars are exactly right and how easy it is to get the equation wrong. There's also some keen insights into Penske's drivers during that era--Mears, Sullivan, Fittipaldi, Unser and Paul Tracy--and Bennett adds an interesting comment about a minor flaw he observed in Penske's otherwise near-perfect operation. Penske's drivers always stayed at different hotels than the team's crewmen and engineers so they rarely enjoyed dinner together and Bennett thinks this was a loss for the team. "I believe we suffered in comparison to teams whose drivers and race engineers spent more time together," he writes. "When I worked for Team Lotus, Ensign and Newman/Haas we always ate with the drivers and stayed in the same accommodation. It's surprising what a driver will remember, and what an engineer can think up, over a good meal and a glass of wine." Bennett also offers a succinct comparison of the different philosophies of Colin Chapman and Roger Penske. "Roger, perhaps prompted by the race team," he writes, "didn't want the hassle of a new, complex system, and I think he was right. Colin, however, would have jumped at the concept and come hell or high water, would have pushed for its development. One the great team owner and organizer; the other the great concept and technical advancement man."  © Tony Matthews But that was the beginning of the end for Penske Cars which went out of business a few years later as the Dallara spec car age arrived. Bennett finished his career working as a consultant to G-Force in the IRL, but he looks back with great fondness on his years through CART's heyday designing Lola and Penske Indy cars. "The '80s and 90s were, I believe," Bennett writes, "the most wonderful period of motor racing, particularly in Champ Car racing based in the USA. The series ran on tracks in North America, Canada, South America, Australia, Japan and on occasion in the UK and Germany. Races were held on street courses, road tracks, one mile short ovals and superspeedways. There was good competition with a variety of cars, engines and tires, and winners were varied and numerous. To my mind the racing and technology was just as interesting and more complex than Formula 1 at the time." Always a very civilized gentleman, Bennett taught me many lessons over the years. He and his longtime companion Sue are very rooted, sensible people who were never seduced in any way by the money, power and glamor of big time motor racing. Bennett's other love is sailing and power boats which he also writes warmly about in his book. It's unfortunate Nigel's book wasn't given a proper final edit leaving too many typographical and spelling errors as well as incorrect years in the text that will be irritating and confusing to any readers who are less than fully-informed. But don't allow these distractions to get in the way of enjoying a great book about motor racing. I highly recommend 'Inspired to Design'. It's available from www.velocebooks.com |

|

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright ~ All Rights Reserved |