The Way It Is/ The Parnelli Jones storyby Gordon Kirby |

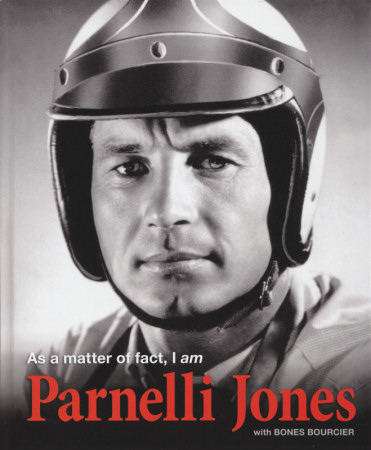

At long last, the definitive biography of Parnelli Jones' life and epic racing career has arrived. Published last month by Coastal 181, 'As a matter of fact, I am Parnelli Jones' was written by veteran racing writer Bones Bourcier who's done a superb job of telling Parnelli's story.

At long last, the definitive biography of Parnelli Jones' life and epic racing career has arrived. Published last month by Coastal 181, 'As a matter of fact, I am Parnelli Jones' was written by veteran racing writer Bones Bourcier who's done a superb job of telling Parnelli's story.

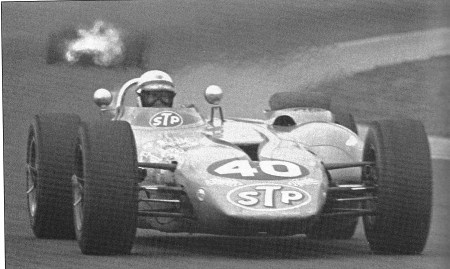

Bourcier introduces each chapter and then stands aside to let Parnelli do the talking. Speaking in his quietly direct and very wise voice, Parnelli draws you in with his enthusiasm, pragmatism and warmth as the book evolves into the story of a smart businessman and loving family man who contrasts sharply with the legendary tough guy image of Parnelli in his heydays during the nineteen-sixties. If anyone defined the American race car driver of the sixties it was Parnelli Jones. Parnelli stands at the pinnacle of the American pantheon with legends from one of the sport's greatest eras like A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, Dan Gurney and Mark Donohue. Rufus Parnelli Jones was a tough, crew-cut hombre with chiselled features and a fearsome, cool-eyed stare. He came up through the rough and tumble world of jalopy and modified stock car racing in southern California and made his mark by winning in stock cars, midget and sprint cars before establishing himself as maybe the fastest of all the great drivers who tackled the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in the sixties.  © Parnelli Jones Collection That was the end of his career in Indy cars, but Parnelli continued to race in Trans-Am, Can-Am and off-road cars and trucks. He won the 1970 Trans-Am championship with a Bud Moore Ford Mustang, beating Mark Donohue and Penske Racing by a single point when the Trans-Am series was one of the USA's top racing series, brimming with manufacturer-backed teams. Parnelli's Trans-Am championship year also launched the Boss Mustang, a concept he's forever identified with which is still being promoted and sold almost half a century later. He also won the Baja 1,000 off-road race in 1970 and '73, setting a record that remains unbroken, and his resume includes four NASCAR stock car victories, the 1964 USAC stock car championship and the 1961 and '62 USAC Sprint car titles. And the likes of Mario Andretti and Bobby and Al Unser say Parnelli was the best driver they've ever seen at Indianapolis where Jones qualified on the first two rows for all seven 500s he started and led five of those races for a total of 492 laps. Then there was his career as a team owner in partnership with Vel Miletich. Vel's Parnelli Jones racing won the Indy 500 with Al Unser in 1970 and '71, as well as three consecutive USAC championships with Unser and Joe Leonard in 1970, '71 and '72 and a total of forty USAC Championship races between 1968-'77. VPJ also produced the first Cosworth-powered Indy car, developed by John Barnard and driven successfully by Al Unser, and a similar F1 car raced by Mario Andretti from late 1974 through early '76. VPJ's cars were usually beautiful and often revolutionary. VPJ also built and developed a series of Ford and Chevrolet off-road trucks for Parnelli to race while he expanded his business interests with Miletich, becoming a very successful Firestone tire distributor and property developer in Southern California. His sons P.J. and Page pursued racing careers and both won races in a variety of cars. P.J. drove for All American Racers in both IMSA and CART and won four IMSA races in 1992 and '93 aboard an AAR Toyota GTP car. PJ also has raced irregularly in NASCAR and IRL. Younger brother Page won a lot of midget races and championships and his career was beginning to take off when he was seriously injured in a midget at Eldora, Ohio in 1994. The accident brought Page's driving career to an end. Today, at seventy-nine, Parnelli remains as sharp as ever, full of ideas and quiet, firm opinions. He knows as much about racing as any man alive and remains energetic and fit, easily able to remember many details from fifty years ago as if it happened yesterday.  © Harry Goode Photo courtesy Gene Crucean Through some hard times Parnelli began to emerge as one of Southern California's fastest, toughest jalopy racers who was not at all averse to using his fists to settle any arguments. By the time he was 21, Jones was able to earn enough money racing jalopies to quit his regular job and become a professional racer. In an era that also gave us great road racers like Dan Gurney, Phill Hill and Richie Ginther, it was a perfect time to be a California racer. "The cars may have been crude, but a lot of good racers came out of Southern California in those days," Parnelli writes about short track jalopy racing in the fifties. "The level of competition contributed to that. It sharpened everybody up. But Mother Nature helped, too. Southern California had great weather, so a promoter could keep his track open nearly all year round. In those days, with most of the cars and parts coming out of junkyards, there wasn't much trouble keeping the car count up. So lots of cars meant lots of drivers, and the nice weather meant lots of chances for good racers to get even better, like cream rising to the top. If you run three times a week through the regular season, and at least once a week all year long, you get pretty fine-tuned. "The other thing is, I think it was an advantage to grow up racing in California because so many of the Indy Car people were based out here. All the famous Indianapolis roadster builders---Frank Kurtis, A.J. Watson, Quin Epperly, Lujie Lesovsky, Eddie Kuzma--had their shops in the Los Angeles area, and those guys were up to speed on what was happening on the short-track scene. They knew about hot young drivers coming up, drivers no one might have noticed if they were racing back East. Or, for that matter, racing in Arkansas, where I'd come from. I was definitely in the right place at the right time." Parnelli's fast driving and aggressive style caught many eyes and he was soon making himself an even bigger name racing NASCAR stock cars. A big break came when he got a ride in Ford dealer Oscar Maples car. Parnelli scored his first NASCAR win in Maples' Ford at the paved, quarter-mile Legion Speedway in Huntington Beach in 1956 and won a NASCAR Grand National road race on an airport in Bremerton, Washington in 1957. Bourcier and Jones also discuss a Grand National race Parnelli is sure he won at Bay Meadows Speedway in San Mateo in '56 only to be placed second by NASCAR officials who missed scoring one of his laps. Vel Miletich was Maples' manager and Parnelli and Miletich became lifelong friends and business partners. Parnelli hauled Maples's car across the country to Darlington in 1956 to run the Southern 500 which was NASCAR's biggest race at the time. He won a bunch more west coast NASCAR races through the late fifties.  © Parnelli Jones Collection From 1961 through '67 Parnelli established himself more often than not as the man to beat at Indianapolis. Like A.J. Foyt and Mario Andretti, his name became synonymous with the Indy 500 and was elevated to new heights when he dominated but failed to finish the last 500 he drove in 1967 with Andy Granatelli's STP turbine. Parnelli also widened his reach, winning the LA Times GP sports car race at Riverside in 1964 aboard one of Carroll Shelby's 'King Cobra' Cooper-Fords and winning a Can-Am heat race at Laguna Seca two years later driving a Lola T70-Chevy for John Mecom. Jones retired from racing open-wheel cars in 1968 but continued his career in Trans-Am and off-road racing. He won the Trans-Am championship for Bud Moore and Ford in 1970 after a furious battle with Mark Donohue and Penske Racing and also showed his mettle in off-road racing, setting a remarkable Baja 1000 record when he won the classic for a second time in 1973 with his pal Bill Stroppe aboard their 'Big Oly' Ford Bronco truck. During this time Parnelli also found success as a team owner in partnership with Vel Miletich. Vel's Parnelli Jones Racing was one of the top Indy car teams through most of the seventies and VPJ also ran a Formula 5000 team for a few years with Mario Andretti and Unser driving, and of course, there was even a VPJ Formula One team from 1974-'76 with Andretti at the wheel. Bourcier completes the story with great interviews, short chapters in fact, with the likes of Andretti, Al Unser and many others including Bobby Unser, A.J. Foyt, Johnny Rutherford and Bud Moore as well as friends and business associates such as Billy Calder, Art Hale, Cary Agajanian and Jim Dilamarter. Bourcier and Parnelli also tell the story of the Jones family life and the racing careers of sons PJ and Page. Both of Parnelli's sons found plenty of success in racing, winning many times in different categories, but PJ was frustrated not to be able to make the right moves at the height of his career while Page was grievously injured in a bad accident in a midget in 1994. The stories of their racing lives and tribulations are also told warmly and generously by Bourcier and Jones as well as P.J. and Page. The final chapter of Bourcier's book is titled 'Elder Statesman'. In this chapter, Parnelli reflects on the sport he loves with some wise words, a few of which I must quote here. "Technology has been good to racing in many ways, especially when it comes to safety," Parnelli writes. "Think about the improvement in helmets, fire suits, fuel cells, fire extinguishers, seat belts, head restraints, and even car construction. And the SAFER barrier has been a huge improvement; every time I see how those walls absorb energy, I'm reminded how much it hurt to hit concrete. Tony George doesn't get enough credit for those SAFER barriers; in his time running things at Indianapolis, he really drove the project forward. "Science and technology have saved a lot of lives. At the same time, science and technology have hurt racing in other areas. In particular, I believe electronics and aerodynamics are taking away the human element that is so much a part of the sport. Fans have always related to drivers, but also to mechanics. The mechanical aspect of racing was something they could appreciate, even if they didn't know how to hold a wrench. They understood the concept of a man building a car and then tinkering to make it go faster. If they happened to go into the pits, they could actually see that tinkering.  © Parnelli Jones Collection "Racing needs to be entertaining. That's something NASCAR, probably more than any other organization, has done right: They've come up with a very entertaining product. Every Sunday there are plenty of cars that can win, and so many different personalities that it's like following a weekly soap opera. "NASCAR has struck a really good balance: The casual fan sees a lot of crashing and banging, the serious fan usually sees a close race, and the participants are involved in something that's a real challenge. "Sure, NASCAR has seen engineering and aerodynamics start to play a bigger role. But compared to Indy Cars, stock car racing has much more room for surprises, because of the human element. The driver and his crew chief are still the biggest parts of the equation. "There have been many Indy Car races in recent years where you knew the winning car owner was going to be Roger Penske or Chip Ganassi, or lately, Michael Andretti. Their teams have great drivers, but they also have the best engineering staffs. That's not a knock on Roger, Chip or Michael; they're just doing things the way they have to be done today. But I'm not sure that way is best for the sport. "Part of the problem with Indy Car racing is that it was run for so long by the team owners, and they act like they're still in charge. The owners are always complaining about the sanctioning body. They fought against Tony George, and as soon as Tony was replaced by Randy Bernard they started fighting against Randy. You never get the sense that everybody's pulling in the same direction. "Indy Car racing would be in better shape today if it had been run all along by a man like Bill France, who founded NASCAR. France was a dictator, and sometimes the competitors would squawk about him, but in the end they knew who the boss was. "Racing cannot be governed by a democracy. It just doesn't work. That's because racers are competitive people, and competitive people are selfish. Anytime racers govern themselves, they end up making decisions based on their own individual interests.  © Parnelli Jones Collection "While I'm on my soapbox, I have a few more thoughts on Indy Car racing. Everyone agrees that safety is a big issue in that form of racing, particularly on oval tracks. I've believed all along that the best solution is a combination of more horsepower and less downforce. For too long we've been in a situation where the cars are underpowered and glued to the track, and the driver keeps the throttle pedal flat on the floor. "Anytime you make it possible for the cars to run wide open, without lifting, you're eliminating a lot of what separates the great drivers from the rest of the pack. Racing should be about driving deeper into the corner than the next guy, and getting back to the throttle sooner. Make the cars trickier to drive--with less downforce and more wheelspin--and we'll find out who's got talent. "I'm not saying the current Indy Car guys aren't talented; just the opposite. There are several really good drivers in that series, and I'd like those guys to be able to show off their talent a bit more. "And here's something I can't figure out: Why is it that whenever a sanctioning body wants to design a new rules package, they go straight to the engineers for suggestions? Every engineer I've ever met wants to build a car that corners better and gave more grip. In other words, a car that's easier to drive. So don't ask those guys." There's much more in the pages of 'As a matter of fact, I am Parnelli Jones'. It's an essential read. You can buy it at www.coastal181.com or www.racemaker.com |

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby Copyright 2013 ~ All Rights Reserved |