The Way It Is/ Bruce Ashmore's concept of the 2011 Indy car

by Gordon Kirby Bruce Ashmore has been involved with Indy car racing for thirty years. He started his engineering career at Lola Cars in his native England in 1976 and was a junior designer on Al Unser's 1978 Triple Crown-winning Lola T500. Ashmore worked his way up to become Lola's chief Indy car designer in the late eighties and early nineties before becoming Reynard's primary, US-based development engineer.

Bruce Ashmore has been involved with Indy car racing for thirty years. He started his engineering career at Lola Cars in his native England in 1976 and was a junior designer on Al Unser's 1978 Triple Crown-winning Lola T500. Ashmore worked his way up to become Lola's chief Indy car designer in the late eighties and early nineties before becoming Reynard's primary, US-based development engineer.

These days, Ashmore is an engineering consultant to C&R Racing in Indianapolis and helped develop the current USAC Silver Crown car. C&R Racing employs fifty people and builds chassis, transmissions, driveline components and cooling systems for a wide range of racing categories including all three major NASCAR divisions, ALMS, Grand-Am, sprint cars and midgets.

For many years Ashmore sat on CART's rules committee and a few years ago he worked with fellow engineers Brian Lisles and Tom Brown, among others, to write a design brief for Champ Car's Panoz spec car. Recently, following some conversations with Honda Performance Development's new boss Eric Berkman, Ashmore was invited to write a 'white paper' for Honda describing his ideas for the Indy car of 2011.

It's interesting that after many years of believing deeply in downforce, Ashmore has discovered that the great god of aerodynamics is the enemy of racing. Ashmore has become a believer, like Mario Andretti, Bobby Rahal and many others, in severely cutting downforce and at the same time increasing power so that the drivers have to lift out of the throttle and maybe even use the brakes for the corners.

"When I was on the CART rules committee back in the eighties and nineties Mario always used to say, 'Get rid of the downforce.'," Ashmore remarks. "I didn't understand what he was saying because we were trying to make the car faster and downforce was so much part of that. Because you've made it faster, you think you've made a better race car but I've learned that's not true.

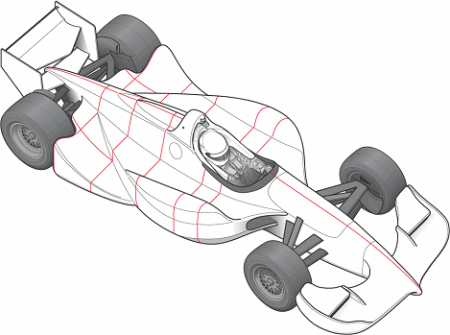

©Paul Laguette

"It's about power to weight, or rather downforce to weight. That's why a NASCAR car can't go around the track flat because it weighs 3,500 pounds and makes maybe 1,200 pounds of downforce. Same thing with a sprint car which weighs 1,800 pounds and makes only two hundred pounds of downforce. An Indy car weighs 2,000 pounds with fuel and driver, and it makes 2,000 pounds of downforce. So you've got to change the rules so it doesn't have anywhere near the downforce it's got now.

"It's a bold move for anybody to make," Ashmore adds. "Seriously reducing the downforce is going to be a tough one because it's going to be such a big change. But many people in the business seem to agree it's worth trying.

"I'd make the car much more rounded so they don't shed so many vortices. The car I've drawn is wrong because it would have too much downforce. It needs to be somewhere around twenty-five percent of where it is now which is 300-500 pounds instead of 2,000 pounds. That's the sort of downforce level you need with a bit more horsepower, probably around 800 horsepower and 1,000 on the road courses. You need to make it so that the lap time is a lot less dependent on the engine or the amount of horsepower and put it more in the drivers' hands."

Ashmore agrees with the IRL's Brian Barnhart that it's necessary to stay with a spec chassis and aerodynamic package until the series can generate the sponsorship to pay for an open or competing chassis formula.

"I'd love to go away from the spec car, but it's about solving your biggest problem," he remarks. "I think the step to an open chassis formula can come later when the series is much healthier commercially. The Champ Car concept car I designed a few years ago is what I'd like to see.

"It needs a bit of tweaking but it's along the lines of what I'd want to see with more rounded edges and the sidepods flush with the outer line of the wheels and bodywork in front of the rear tires. That way the drivers can run close to each other. I don't understand why people don't seem to understand this point."

The matter of devising the right bodywork rules to prevent interlocking wheels and flying cars is one of Ashmore's favorite causes, and we'll get back to it. But before covering that ground he wanted to make the point that with the overall downforce slashed the cars would be less disturbed in traffic because they would be less dependent on the wings and downforce and therefore much more capable of racing and passing. He also believes in devising wings that produce little or no downforce and reducing the aerodynamic vortices generated by the car.

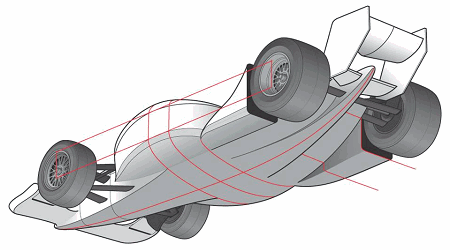

"The biggest vortices come off the tires because the top of the tires are going forward in the opposite direction to the race car. If you had some type of thin, dart-like wing on the back it would catch the two front vortices and the inside rear, and you wouldn't have the vortex off the rear wing either.

© Paul Laguette

"The ideal thing would be to have no downforce with low drag and stable, too, with a dart-like wing on the back. Then you could have more horsepower because the drivers would not be running flat in the corners."

Ashmore makes the point that whatever the rules, it will take a strong, smart sanctioning body with plenty of resources to make them work.

"When you've taken all the shapes off the car that produce downforce, you've got to have a very strong governing body that understands aerodynamics," Ashmore comments. "The moment they see something that produces downforce they've got to get rid of it.

"There are a lot of clever people out there and they will always try to find downforce. You're not going to unlearn how to use a wind tunnel. It doesn't matter whether you call it a wind tunnel or CFD, or whatever. You will always come up with a device to measure downforce and aerodynamics.

"So you have to have an intelligent technical department within the series that does their own wind tunnel testing to control the teams. They've got to ban things people want to try. They've got to be like NASCAR and say, 'Don't come back with that device.' They have to say, 'Take that off. We're not going to let you race it this weekend. We're going to test it and see what it does. If it produces downforce you're never going to use it or bring it back to the track again.' It's really as simple as that. If NASCAR doesn't understand something, they ban it."

Ashmore believes that in today's world the engineering skills required can be outsourced by the sanctioning body.

"You've got lots of engineering companies today in Indianapolis and Charlotte that would do the work for you," he observes. "You don't have to have any doubt anymore. You can go and rent some professional people to find out."

Returning to his favorite subject of extending the bodywork to the outer edge of the wheels and tires to prevent accidents, Ashmore talked about the lessons learned from USAC's Silver Crown car.

"One feature on the Silver Crown car that I've been campaigning for years to introduce to Indy car racing is the sidepods are the same width as the outside dimension of the tires so if you run alongside each other you don't get interlocking wheels. This feature was on the design brief for the Panoz Champ Car but Panoz didn't do it. It was top of the list at all the meetings that I went to with Brian Lisles and Tom Brown and they just flat didn't do it.

"We've proved it works in the Silver Crown series because cars have come in with wheel marks on the side of the side pod but they haven't crashed. The wheels didn't interlock and they didn't go flying. They could get alongside each other and there were lead changes and the car in front didn't affect the car behind so much."

Ashmore points to the Marco Andretti-Ryan Hunter-Reay crash in Texas as a classic example of cars being launched by interlocking wheels.

"It was the same crash we've seen many times," he remarked. "Marco's right front tire got in front of Hunter-Reay's left rear and the moment they touched the cars went sideways and went up into the wall. The commentators blamed it on Marco pinching Hunter-Reay and Hunter-Reay going below the white line. But it wasn't that. It was because the wheels touched, not because Hunter-Reay went down below the white line.

"If the bodywork had been there they wouldn't have been launched like that. Hunter-Reay could have still gone down to the white line and even if he had slid up into the other car they wouldn't have crashed. They would have both made it and Marco would probably have come out of the corner ahead because the car down below would have lost speed. But instead they touched wheels and launched themselves because the wheels are open and exposed and the tires can interlock and launch one car off the other.

"I don't think getting close to each other is the problem," he adds. "You need to design the rules so the drivers can get close. The idea is to race closely. The cars do need to be able to touch each other. So you need to design the cars so they can run close to each other. The suspension needs to be stronger so they don't fold up and the wings need to be stronger so they don't fall off."

Ashmore hopes the 2011 IndyCar formula will be compelling enough to attract some competing engine manufacturers into the series.

"I think we do want multiple manufacturers because you need different brands," he says. "People support Ford or Dodge, Chevy or Toyota. If you run the series properly, it's the perfect marketing platform for the car companies. It works in NASCAR and Formula 1 and sports car racing. Why not in IndyCar?"

Ashmore believes a small-capacity, twin-turbo V-6 is the way to go.

"A turbo engine is good for controlling noise levels at arena-type tracks and you can also turn the boost up, or down, for road courses or ovals," he comments. "My suggestion is to go for twin turbos and put one turbo/wastegate assembly in each sidepod. You don't want to go back to a single turbo located in the bellhousing because that just eats up the gearbox and is not efficient.

"When we sunk the turbo down into the gearbox it didn't make the car better. It made it faster, but not better. We had to put a cooler on the gearbox and all the components and the suspension joints wore out because they ran so hot.

"Definitely a V-6 is the way to go because you've got less bits," Ashmore adds. "It'll be less complicated and less expensive. I think two liters is a bit too big. I'd say it probably needs to be about 1.5 liters. We went through this before in the CART days trying to make a decision on a new engine formula and we were bouncing between 1.5 and 1.8 liters. So I'd say a 1.5 liter, twin turbo V-6 with the turbos in the sidepods. It would make a very nice, tidy little package."

So that's Bruce Ashmore's comprehensive plan for the Indy car of 2011. I hope everyone involved in trying to recreate Indy car racing gives his 'white paper' a close read.

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright 2008 ~ All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2008 ~ All Rights Reserved

Top of Page