A Fond Farewell

by Gordon Kirbyillustrated by Paul Webb

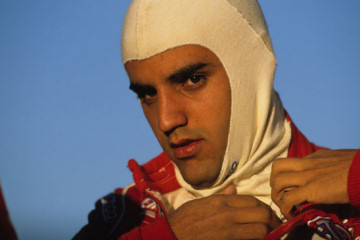

Juan Montoya leads the CART field at Rio de Janeiro in 1999 The telegram arrived thirty-two years ago in February of 1973. It was from Richard Feast, the editor of Autosport at the time. "Pete Lyons coming over to cover F1," the telegram read. "Would like you to take over as American editor."

I had written occasionally for Autosport from my home in Toronto since 1968 and had badgered first Simon Taylor and then Feast about doing more work for the magazine. I started in the business doing a little bit of everything after dropping out of school to work on racing cars and write about them too. I worked part time for Gary Magwood, a Formula Ford racer who owned a race preparaton shop and was the Hawke FF1600 distributor for Canada. I also helped out another young racer named Brian Stewart who raced Formula Vees and then Fords. Both Magwood and Stewart went on to win the Canadian FF championship.

I worked part-time also for 'Wheelspin News', a weekly racing newspaper published in a suburb of Toronto by drag racing and short track promoter 'Dizzy Dean' Murray. I had talked Simon Taylor into making me Autosport's Canadian correspondent in 1968 and using my thin Autosport connection as proof that I knew what I was talking about I convinced Murray to make me Wheelspin's road racing editor. I wrote my first feature for Autosport in 1969 about wealthy Canadian department store heir George Eaton who had made a name for himself in the CanAm and was about to try Formula 1 with BRM.

Around the same time I met David Loring, a teen-aged Formula Vee driver from Massachusets who was too young to drive in SCCA races in the USA. David and I became friends and he moved up to Formula Ford in 1970 and had a great year in '71, winning twenty-one races and four championships, including the Canadian and IMSA FF titles. He also won a Quebec-based Jim Russell championship which boasted a season of Formula 3 in England as a prize with a factory-backed Lotus. But the F3 car was a fiction. Instead we were paid a thousand pounds and used the money plus the profit from the sale of David's two Caldwell FFs to race once again in Formula Ford with a Merlyn.

David won five races in the UK that year and set a track record at Mallory Park that stood for five years but he also ran into a lot of bad luck. Typically, in the first Formula Ford Festival run at Snetterton in November he duelled for the lead with eventual winner Ian Taylor but inadvertently pulled off his visor when he removed a rip-off shield. Struggling to see without a visor in light rain and with a misting spray of oil coming from Taylor's car he fell back to finish a deeply disappointed fourth.

Formula Ford in its' heyday, Brands Hatch 1972. David Loring (#55) on

the inside, one wheel in the grass Photo courtesy David Loring collection

David regrouped first in Formula Ford, then Formula Atlantic, winning the SCCA's 1978 FF1600 title in an Eagle he built and campaigned for All American Racers and also winning his class at Sebring three times in GTU and GTO cars.

When Feast's telegram arrived in the middle of a snowy February I accepted his offer immediately and my career shifted from sponsor-chasing and raggedy-ann team managing to becoming a full-time racing journalist and writer. I jumped into the first of a series of Ford and Dodge vans to begin touring the United States and Canada while working for Autosport and for AutoWeek in the USA, as well as anyone else who would buy my stories.

In those days the job description for Autosport included covering the SCCA's CanAm and Formula 5000 series as well as the Indy 500 and USAC's two other 500-mile races, NASCAR's Daytona 500 and the Daytona 24 hours and Sebring twelve hours. It was an eclectic mixture of races, cars, venues and personalities and I enjoyed it immensely.

Looking back, my first season covering North America for Autosport was quite remarkable. Started in 1966, the original, unlimited CanAm was the most spectacular road racing series ever run in the United States and Canada although it was entering its final years in 1973 after the McLaren team pulled out as the turbocharged Porsche 917/10 and 917/30 CanAm cars blew the naturally-aspirated Chevrolet-powered McLarens out of the water.

In '73 I witnessed Mark Donohue dominate the CanAm in Roger Penske's incredible 917/30K with more than a thousand horsepower on tap. Donohue was an excellent driver and superb engineer who gave life to Penske Racing and I well remember him breaking Denny Hulme's track record at Elkhart Lake by a whopping seven seconds as he became the first man to lap the classic, four-mile Wisconsin road course in under two minutes. Eleven years would pass before Mario Andretti broke Donohue's standard in 1984 driving a Newman/Haas Lola Champ car.

Donohue's strongest challengers that year were a pair of year-old 917/10s driven by George Follmer and Jody Scheckter. Jody was fresh out of Formula 3 and about to break into F1 with McLaren and in those days he was a ferociously wild driver. He also raced in the SCCA's Formula 5000 series in 1973 and I saw plenty of tire-smoking, arm-sawing moments from him that season as well as a few spectacular accidents from which he emerged a little tousled, but grinning only half-sheepishly, and mercifully always uninjured. Jody was lucky to survive those days and emerge a few years later as a more conservative, mature world champion with Ferrari.

Donohue's strongest challengers that year were a pair of year-old 917/10s driven by George Follmer and Jody Scheckter. Jody was fresh out of Formula 3 and about to break into F1 with McLaren and in those days he was a ferociously wild driver. He also raced in the SCCA's Formula 5000 series in 1973 and I saw plenty of tire-smoking, arm-sawing moments from him that season as well as a few spectacular accidents from which he emerged a little tousled, but grinning only half-sheepishly, and mercifully always uninjured. Jody was lucky to survive those days and emerge a few years later as a more conservative, mature world champion with Ferrari.

Meanwhile, with their mission accomplished, Porsche and Penske pulled out of the CanAm at the end of '73 and the series survived only one more year. The original CanAm's final year was dominated by Jackie Oliver and George Follmer driving a pair of UOP Shadow-Chevies for the only professional team left in the once-great series. Before the last race of 1974 at Riverside could take place, the SCCA pulled the plug on the CanAm. It was the first of five major racing series--CanAm, F5000, the USAC championship, IMSA and CART--I would see euthanized during my career with Autosport.

The original CanAm failed because the SCCA couldn't manage the rules in a time of rapidly-evolving technology and also because the club couldn't manage the manufacturers or properly promote or market the series. In the end these same factors have resulted in the failure of almost the entire sport in America beyond NASCAR and drag racing. From that perspective, my thirty-two year run with Autosport has been extremely sobering.

The original CanAm failed because the SCCA couldn't manage the rules in a time of rapidly-evolving technology and also because the club couldn't manage the manufacturers or properly promote or market the series. In the end these same factors have resulted in the failure of almost the entire sport in America beyond NASCAR and drag racing. From that perspective, my thirty-two year run with Autosport has been extremely sobering.

Which brings us to the Indianapolis 500 and the USAC Championship. I had watched the Indy 500 in movie theaters in the sixties and subsequently on TV, but I had never covered a superspeedway oval race when I first arrived at Indianapolis in May of '73. Right away the place struck me, quite literally, as deadly serious. Bear in mind that Bobby Unser and the spectacular 1972 Eagle-turbo Offy had broken the track record the previous year by seventeen mph, the biggest leap in speed in the Speedway's history. At the Ontario Motor Speedway in '72 Unser and teammate Jerry Grant became the first men to lap a closed course at over 200 mph and watching the USAC cars perform on an oval for the first time at Indianapolis in the spring of '73 gave new meaning to words like fear and respect.

It turned out that the '73 Indy 500 was a disastrous event. Veteran Art Pollard was killed in practice and the race itself debilitated into a horror show, taking three days to run because of repeated rain storms and resulting in the fiery death of Swede Savage and a crewman and serious burns and other injuries to Salt Walther in one of three attempts to start the race. The race was eventually red-flagged at two-thirds distance and the next month USAC slashed fuel tank capacity in half and began to restrict the width of the massive rear wings that had proliferated from 1971 through early '73.

This was the beginning of the modern age of racing as more and more limitations were placed on every aspect of racing car design in repeated and often vain attempts to restrain both lap speeds and costs. It wasn't long before the many great innovations and spectacular racing cars of the sixties and seventies were replaced by the increasing spec-car syndrome which has swept through the sport so that today almost every aspect of chassis, engine and aerodynamics are defined by the rulebook in all forms of racing, F1 included.

For a few years USAC considered adopting the SCCA's stock-block F5000 formula for Championship or Indy car racing. USAC and SCCA co-sanctioned America's F5000 series in 1975 and '76 and the category boomed in those years with almost fifty cars showing up for the inaugural Long Beach GP F5000 race in the fall of 1975. Brit Brian Redman was the scourge of F5000, winning the championship for three years in a row as well as the Long Beach inaugural for Haas/Hall Racing. Redman beat the likes of Mario Andretti and Al Unser, a pair of USAC stars who ran the F5000 series for a few years for the Vel's Parnelli Jones team.

'Our Brian' was and is a fine fellow, a tremendous raconteur, humorist and writer, who is probably the most unrecognized great driver from those days simply because after dabbling in it on two occasions he decided F1 wasn't for him. He preferred to race elsewhere but Redman's record of diversity in international sports car racing, IMSA and F5000 is as good as anyone's.

Then, of course, there was Gilles Villeneuve who I had the great pleasure to watch and cover as he came up through Formula Ford and Formula Atlantic. Even then Gilles's impish sense of humour and spectacular driving style stood out. Villeneuve spent four years in Formula Atlantic, driving for Kris Harrison's Ecurie Canada team in 1974, '76 and '77 and running his own car in 1975. Thirty years later it's impossible to imagine a Formula Atlantic driver jumping directly to F1 but that's exactly what Gilles did after winning the Atlantic championship in 1976 and beating F1 stars James Hunt, Alan Jones and Patrick Depailler at Three Rivers.

Back in those days the Atlantic series was booming with thirty and forty car fields and I will always remember Gilles and Keke Rosberg banging wheels as they drove side-by-side through the first turn at Mosport at the start of the opening Atlantic race of 1977. They were deeply serious rivals throughout the year, neither speaking to the other as they battled for the attention of F1 team managers.

At Quebec City at the end of the year Villeneuve crashed two cars in practice as he went all-out to prevent Rosberg from stealing the championship. Gilles had made his F1 debut with McLaren earlier in the summer but was in the midst of been traded to Ferrari by Teddy Mayer while he was deeply intent on wrapping-up his second consecutive Atlantic title. After a disastrous practice and qualifying in Quebec City he came through the field to win the race and the championship after Bobby Rahal's engine failed.

On a wall of my office at home hangs a color photograph taken by my friend Paul Webb of Rosberg totally sideways in his pink Fred Opert Chevron sponsored by Excita condoms. The car features a dildo attached to the nose and Keke is seriously scraping the wall at Quebec City with his left rear wheel as he throws the car onto the pitstraight. In those pre-ground effect days Atlantic cars provided a perfect balance of horsepower and tire grip. It was a superb training category that totally prepared guys like Gilles and Keke for F1 and also offered the fans spectacular raw-boned racing. But thirty years of mismanagement of the sport both technically and promotionally has left Atlantic and the entire open-wheel ladder system in the United States at the brink of death's door.

On a wall of my office at home hangs a color photograph taken by my friend Paul Webb of Rosberg totally sideways in his pink Fred Opert Chevron sponsored by Excita condoms. The car features a dildo attached to the nose and Keke is seriously scraping the wall at Quebec City with his left rear wheel as he throws the car onto the pitstraight. In those pre-ground effect days Atlantic cars provided a perfect balance of horsepower and tire grip. It was a superb training category that totally prepared guys like Gilles and Keke for F1 and also offered the fans spectacular raw-boned racing. But thirty years of mismanagement of the sport both technically and promotionally has left Atlantic and the entire open-wheel ladder system in the United States at the brink of death's door.

And I must mention one of Villeneuve's rare 'new era' CanAm appearances, driving a Wolf CanAm car in two races in 1977 after Chris Amon had decided to retire. At the end of 1976 the SCCA, in their wisdom, decided to attempt to bring back the glory days of the CanAm by putting fenders on F5000 cars and calling them 'new era' CanAm cars. I remember watching Gilles qualify the ungainly Wolf at Mosport, typically using all the curb and a good deal of the grass verge as he wrestled the largely brakeless car around the track. Back in the paddock he was grinning broadly as we talked.

"The brakes on that thing look terrible!" I said. "It's not that bad," Gilles shrugged before grinning broadly. "You don't need brakes to go fast. Sometimes it's better just to slide the car to stop it. If you do it right, you're in perfect shape to get on the throttle and power your way out of the corner."

That was Gilles Villeneuve to a tee.

Another story worth telling is about the first time I met Richard Petty, NASCAR's original seven-time champion, at Daytona in 1975. I introduced myself and the 'King' politely asked if I could wait for five minutes he'd be back and we could do an interview. Sure enough, he returned a few minutes later, flashing that famous grin and suggesting we go over to his rental car. An hour and a half later we emerged after a thoroughly charming and informative discussion about himself, his father Lee, the Petty family and NASCAR. I was impressed for life.

This was long before the days of public relations people when this kind of thing was normal and in this way NASCAR and professional motor racing as a whole has changed out of all recognition. Today in NASCAR the drivers are kept far from the press and fans. More than any other form of racing the fleets of pr people in NASCAR serve as a deep buffer between their clients and the press. In recent years in fact, the hundred-strong driver and car owner motorhome parking lot at Daytona has been protected by a stout fence emblazoned at intervals with signs proclaiming, 'No Media Permitted Beyond This Point'. Even Formula 1 is devoid of such an exalted area!

This was long before the days of public relations people when this kind of thing was normal and in this way NASCAR and professional motor racing as a whole has changed out of all recognition. Today in NASCAR the drivers are kept far from the press and fans. More than any other form of racing the fleets of pr people in NASCAR serve as a deep buffer between their clients and the press. In recent years in fact, the hundred-strong driver and car owner motorhome parking lot at Daytona has been protected by a stout fence emblazoned at intervals with signs proclaiming, 'No Media Permitted Beyond This Point'. Even Formula 1 is devoid of such an exalted area!

Having made this point, it remains indubitably true that NASCAR is motor racing's great success story. I take my hat off to Bill France Jr and his late father Bill Sr not only for building the world's healthiest form of racing but also constructing an equally strong ladder system through the Busch and Truck series and across the many reaches of the USA to the grass roots level with regional and local NASCAR championships. Since the Frances opened the high-banked Daytona Speedway in 1959 they have steadily expanded their form of the sport, building a complete system as well as an unequalled management and marketing structure while keeping control of the competing manufacturers both technically and in how and where they spend their money.

In the meantime a rabble of squabbling parties, including the SCCA, USAC, IMSA, CART and the IRL have combined over the years to decimate the majority of the wide sweep of the rest of American circuit racing. I'm afraid to say that arrogance, greed, hypocrisy and the lust for power have left us with a bleak field of failed visions and the utter destruction of the ladder system. In America today, Champ or Indy car racing and sports car racing have dwindled to being the country's least relevant sports. Each of Champ Car, IRL, ALMS and GrandAm are barely covered in the nation's newspapers wth small crowds at all but a few races and laughably tiny TV audiences.

I can tell you that the greatest drivers I've had the good fortune to know like Mario Andretti, Dan Gurney, Bobby Unser, Parnelli Jones and Rick Mears are deeply saddened, even broken-hearted by what has happened to the sport in America over the past ten years. It's been diminished and devalued and at the same time the final vestiges of technological intrigue have been squeezed out of the rulebook as the sport has devolved, NASCAR-like, to the lowest common denominator. Without doubt, racing's great revolutionary days of the sixties and seventies are gone forever and with them the magic that made the Indy 500 and the original CanAm such great things has irretrievably faded.

Can that magical whiff be recreated? In a NASCAR-dominated world it's a tremendous challenge for each of Champ Car, IRL, ALMS and GrandAm. I wish them all good luck!

I was also asked by Autosport to select the best drivers, tracks and cars I had the pleasure to enjoy over the years. Here's my choice of the best drivers:

Andretti & Gurney top the list

Without question the greatest racing driver I've had the pleasure to cover and know is Mario Andretti. He raced and won in almost every conceivable type of car known to man and has gone on to become one of the sport's finest ambassadors.

The greatest overall racing man I've encountered most assuredly is Dan Gurney. Dan's equally diverse driving career preceeded my time with Autosport but I witnessed much of his remarkable second career as a team owner, car builder and innovator. All American Racers' long line of Eagle Indy and GTP cars were among the finest, most beautifully-built, ground-breaking racing cars of the last forty years. To me, Dan's spirit of adventure and innovation is what racing is all about.

The greatest character among the great drivers I've known most certainly is Bobby Unser. He was a tremendously forceful driver, as aggressive as anyone at playing the rules to the maximum and, of course, a truly independent thinker. Bobby is the kind of larger-than-life character that is desperately missing from racing today.

The greatest character among the great drivers I've known most certainly is Bobby Unser. He was a tremendously forceful driver, as aggressive as anyone at playing the rules to the maximum and, of course, a truly independent thinker. Bobby is the kind of larger-than-life character that is desperately missing from racing today.

His younger brother Al is a very different personality, almost diametrically opposed. But he was an even better driver than Bobby--smoother, a great stylist in fact, and much more cagey.

Al's son Al Jr was an equally great driver, often superb on raceday, and very versatile too, winning long-distance IMSA races with Al Holbert and Derek Bell, and beating Dale Earnhardt in IROC cars. Al's career was sadly darkened at the end by his problems with alcohol but his talent and accomplishments should not be devalued.

Al's son Al Jr was an equally great driver, often superb on raceday, and very versatile too, winning long-distance IMSA races with Al Holbert and Derek Bell, and beating Dale Earnhardt in IROC cars. Al's career was sadly darkened at the end by his problems with alcohol but his talent and accomplishments should not be devalued.

His great contemporary Michael Andretti made his reputation as an aggressive youngster, much like his father had twenty years earlier. As Mario always said, the fire burned in Michael's heart, and that was the key factor that made him a great driver.

Rick Mears was a sublime talent, a genius of throttle control and smooth, precise driving. Mears scored a superb fourth Indy 500 win in 1991, beating Michael with a memorably magnificent outside pass in turn one. Then there was a superb but unsuccessful attempt to catch and pass Gordon Johncock in the closing laps of the 1982 Indy 500. It's the only time I recall the sounds of the engines being drowned by the roar of the crowd.

Beyond Champ car racing there were Gilles Villeneuve and Keke Rosberg, highly-spirited racers both, and good men too, who I liked a great deal. Keke remains a fine fellow who doesn't seem to get the historical credit he deserves but anyone who saw some of his spectacular performances in Atlantic and CanAm cars knows what a trmendous racer Rosberg was.

Beyond Champ car racing there were Gilles Villeneuve and Keke Rosberg, highly-spirited racers both, and good men too, who I liked a great deal. Keke remains a fine fellow who doesn't seem to get the historical credit he deserves but anyone who saw some of his spectacular performances in Atlantic and CanAm cars knows what a trmendous racer Rosberg was.

Further afield are the best from NASCAR. I put David Pearson at the top of that list. 'The Silver Fox' was as sublime a talent as Mears and an equally clean driver. Pearson only ran the full schedule and went after NASCAR's championship three times, but he won the title every time he tried.

One of the most ferocious racers I ever saw was Cale Yarborough, a three-time NASCAR champion in the seventies with Junior Johnson's team. Yarborough and his oft-rival Bobby Allison were two of the toughest, fastest, most ruthless drivers NASCAR has produced.

Seven-times NASCAR champion Dale Earnhardt was in their league but as Pearson will tell you Earnhardt's penchant for 'using the fender' meant that prior to his deification at Daytona in 2001 his reputation among his rivals was trenchantly contentious.

Seven-times NASCAR champion Dale Earnhardt was in their league but as Pearson will tell you Earnhardt's penchant for 'using the fender' meant that prior to his deification at Daytona in 2001 his reputation among his rivals was trenchantly contentious.

As well as Mark Donohue and Brian Redman, who received their just praise elsewhere in this piece, I have to mention Al Holbert, an excellent IMSA driver and team boss who tried other categories, including CART and NASCAR, and was also good man.

I must also mention Emerson Fittipaldi and Bobby Rahal. Emerson opened the flood of international interest in CART when he arrived on the scene in 1984, three years after retiring from F1, and went on to become a true maestro of Indy car racing. Rahal fought with Gilles and Keke in his early days, raced F3 and F2 in Europe, and was also quite successful in IMSA and international sports car racing as well as in CART.

From more contemporary times Alex Zanardi stands out as the great character and personality as well as a fantastic driver and crowd pleaser. It's a shame he was never seen at his best in F1, but Zanardi the man transcends all as an inspiration in how to live.

From more contemporary times Alex Zanardi stands out as the great character and personality as well as a fantastic driver and crowd pleaser. It's a shame he was never seen at his best in F1, but Zanardi the man transcends all as an inspiration in how to live.

Greg Moore was a tremendous talent who shone brightly for a brief period of time, both as a driver and a human being, before his untimely death in the closing CART race of 1999 at the California Speedway.

Juan Montoya won the championship that afternoon, barely defeating Moore's great friend Dario Franchitti on a dark day. Montoya of course was exciting and entertaining to cover and clearly a very exceptional talent from the first laps I saw him drive.

I also have to mention Cristiano da Matta and Paul Tracy. Da Matta is one of the most motivated drivers I've ever met and is very cool and analytical as well as being a thoroughly good man who was underappreciated by F1. Cristiano is delighted to be back in Champ Car and is a key personality in the hoped-for redevelopment of the series.

I also have to mention Cristiano da Matta and Paul Tracy. Da Matta is one of the most motivated drivers I've ever met and is very cool and analytical as well as being a thoroughly good man who was underappreciated by F1. Cristiano is delighted to be back in Champ Car and is a key personality in the hoped-for redevelopment of the series.

Tracy is another great fighter, a man who inspires his fans on his best days, and in today's sadly Lilliputian world of American open-wheel racing he stands out as the driver with the most powerful identity with the public.

And Sebastien Bourdais showed tremendous talent in winning consecutive Champ Car titles in 2004 and '05. Bourdais is a superb driver and racer and a great technician and thinker as well. He's as good as they come.

Here's my choice of ten best tracks:

Here's my choice of ten best tracks:Elkhart Lake: The grand-daddy of America's permanent road circuits, Road America is fifty years old this year [2005] and remains true to its original self, improved somewhat, but unadulterated by a single chicane or redesigned corner through its magnificent four miles.

Mosport: My old home track has recently been refurbished and like Elkhart is unchanged from it's original 1961 layout. No less an authority than Dan Gurney refers to Mosport as the track in North America that is most like the Nurburgring, albeit much shorter. A tremendous and fitting compliment.

Bridgehampton: No longer with us, Bridgehampton's location in the ultra-chic, ultra-expensive Hamptons on New York's Long Island meant it would never survive. But it was a great track with fast, swooping corners diving through the sand dunes within sight of Long Island Sound.

Riverside: The west coast's version of Bridgehampton lasted longer, from 1957-'88, before it was overtaken by greater LA's urban sprawl. But Riverside was another driver's track with fast, sweeping turns through the desert sand, which drew big crowds for many years and helped make road racing a big thing in LA and Hollywood from the fities through the eighties.

Laguna Seca: Substantially revamped in 1988, the current track retains much of the old circuit and is a fearsome physical test, one of the toughest in the business, although fearsomely difficult for passing. It's also located on the beautiful Monterey bay and peninsula south of San Francisco.

Laguna Seca: Substantially revamped in 1988, the current track retains much of the old circuit and is a fearsome physical test, one of the toughest in the business, although fearsomely difficult for passing. It's also located on the beautiful Monterey bay and peninsula south of San Francisco.

St Jovite: Also recently refurbished this fine road circuit at Mount Tremblant in Quebec's Laurentian Mountains is in the same class as the five previous tracks. St Jovite's long, diving first turn provides some of the finest spectating you'll ever enjoy.

Milwaukee: The flat Milwaukee Mile oval in suburban Milwaukee is the world's oldest racetrack. Opened in 1905 as a dirt track it was paved in 1954 and is one of the few tracks that retains a connection to the USA's oval racing past.

Motegi: More than a dozen new superspeedways were built across the USA during the nineties but the best of all the new tracks that came to life during that Gilded Age was Honda's Motegi oval in the mountains north of Tokyo. The track was deliberately designed to produce exciting rather than the boring racing produced by so many of America's modern cookie-cutter ovals.

Surfers Paradise: Despite the likes of Long Beach and Toronto, the best street track I've seen is Surfers on Australia's Gold Coast. It's the longest, fastest street circuit Champ Car races on with a high quality wall and safety system and simply the best overall setting and fan turn-out.

Surfers Paradise: Despite the likes of Long Beach and Toronto, the best street track I've seen is Surfers on Australia's Gold Coast. It's the longest, fastest street circuit Champ Car races on with a high quality wall and safety system and simply the best overall setting and fan turn-out.

Westwood: Rocks and boulders laid in wait just feet from the edge of the this demanding little road course in suburban Vancouver. In the seventies, from a driver's point of view at least, Westwood was the equal of Mosport and St Jovite until it too was engulfed by urban sprawl. A housing development and shopping mall have occupied the site for many years.

And these are my ten best cars:

Porsche 917/30K: Simply the most awesome racing car I've seen raced in anger.

'72 Eagle-turbo Offy: All American Racers' record-breaking Roman Slobodynskyj-designed machine was the dominant USAC Champ car for almost five years from 1972-'76.

Lola T332C F5000 car and T333CS CanAm version: A rather pedestrian but extremely effective, multi-purpose production racing car with a long, varied lifespan.

March 76B/Chevron B34/Ralt RT1: Classic, pre-ground-effect Formula Atlantic cars from the category's heyday.

Parnelli VPJ6B/C-turbo Cosworth: John Barnard's first big success broke the four-cylinder Offenhauser's long-standing dominance of USAC Championship racing.

Chaparral 2K-turbo Cosworth: Another Barnard design, this one for Jim Hall, which was the first clean sheet of paper ground-effect Indy or Champ car.

Lola T87/00-turbo Ilmor/Chevy: The definitive Indy car of the late eighties and early nineties. Mario Andretti dominated but did not finish the '87 Indy 500 with this car and liked it so much he also raced it in the three 500-mile races in 1988.

Lola T87/00-turbo Ilmor/Chevy: The definitive Indy car of the late eighties and early nineties. Mario Andretti dominated but did not finish the '87 Indy 500 with this car and liked it so much he also raced it in the three 500-mile races in 1988.

Eagle mk III-turbo Toyota GTP car: Blew off Jaguar, Nissan and Porsche as it established a record of nineteen consecutive wins in IMSA from 1991-'93 with Juan Fangio II and P.J. Jones driving.

Reynard 98I-turbo Honda/Bridgestone: Adrian Reynard was fleetingly the master of the production racing car business, like Robin Herd and March before him. This car was the apotheosis of the Reynard art.

Lola B2/00-turbo Ford/Cosworth: The current traction control-free, 'spec' Champ Car is an intriguing and possibly noble exercise in cost and technology control while maintaining a basic level of forward-thinking technology.

Lola B2/00-turbo Ford/Cosworth: The current traction control-free, 'spec' Champ Car is an intriguing and possibly noble exercise in cost and technology control while maintaining a basic level of forward-thinking technology.

Mario Andrettt on GK:

From my standpoint, Gordon is one those savvy old professionals in our sport - certainly one of my favourite journalists, and one I've always looked forward to reading. He and I have always gotten along well, and I've always enjoyed his perspectives on different situations, because he's opinionated to the point that it makes reading his stories interesting and thought-provoking.

The thing is, I think Gordon really (itals) gets (end itals) it.

He understands the sport very, very, well - and all its disciplines, too, not just the one he specialises in. His knowledge of it is huge, no question about it, and he always gave a very good account, to his readers in Europe, of what was going on in the USA.

What I really liked, too, was that Gordon was never afraid to say what he thought - there aren't enough journalists prepared to do that, in my opinion. I think there's a very fine line between trying to ram through your own philosophy on things and stating your opinion firmly on something you really believe in - and I think Gordon walked that line pretty well, I must say. Mind you, maybe to some extent I think that because he and I tend to have similar opinions!

Put it this way, I liked the fact that Gordon never had 'blinders' on, that he always understood the bigger picture, that he always said what he thought. I'm one of his fans! If he's not going to be writing for Autosport any longer, his work is going to be missed, that's for sure.

Put it this way, I liked the fact that Gordon never had 'blinders' on, that he always understood the bigger picture, that he always said what he thought. I'm one of his fans! If he's not going to be writing for Autosport any longer, his work is going to be missed, that's for sure.

Nigel Roebuck, Autosport's veteran Grand Prix writer:

"Where's GK?" I said to a mutual friend in the Milwaukee paddock one morning. "Oh," came the smiling reply, "having an argument someplace..."

Kirby was, is, and will be always be, a man with strong opinions about racing, about life in general, and maybe that's one the reasons why we've always got along so well. We met, I suppose, in the early '70s, and have been close friends ever since.

It doesn't hurt, of course, that we tend to hold similar views on this sport, being very much at the 'purist' end of the spectrum, rather than the 'showbiz' end. Perhaps for that reason, like me, Gordon always much enjoyed the company of Denis Jenkinson, and indeed they always had much in common, both bearded, both bachelors, both living in the back of beyond, both irreverent, both excellent company, both obsessed with racing- and both able to spot a phoney at 50 paces.

Like Mario, I've always respected Gordon for writing exactly what he thinks, for not being afraid to rock the boat, even though he knows - as we all know - that it's not necessarily the way to a quiet life. Beware the journalist who is 'everyone's friend'. He's like a racing driver who never damaged a car.

No one who knows Kirby doubts for a second his deep love of this sport, or that it is from there that his passionate, opinionated, writings stem. He has been in this for the long haul, and if - like anyone of long experience - not all the changes in motor racing have been to his taste, his essential enthusiasm for it has never waned.

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby & Paul Webb ~ Words and Images

Copyright 2006 ~ All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2006 ~ All Rights Reserved

Top of Page