The Way It is/ Reinventing racing's spectacleby Gordon Kirby |

Most sports are very simple. They require little more than a stick, a bat or a ball. Essentially, they're the same today as they were 100 years ago. Whether it's football, baseball, basketball, soccer, golf, tennis, ice hockey, track and field, etc. the basics of the sport and the nature of the spectacle remain unchanged.

Most sports are very simple. They require little more than a stick, a bat or a ball. Essentially, they're the same today as they were 100 years ago. Whether it's football, baseball, basketball, soccer, golf, tennis, ice hockey, track and field, etc. the basics of the sport and the nature of the spectacle remain unchanged.

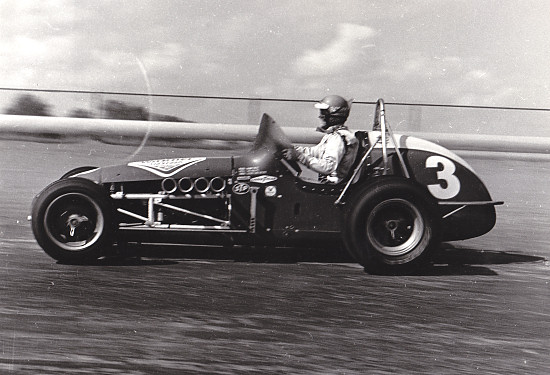

Not so in motor racing. We've been through multiple technical revolutions over the last 100 years so that today's machines are completely different in concept, appearance and performance from the giant, lumbering behemoths of the sport's early days. Unlike other sports the nature of motor racing's spectacle has changed many times over the decades. Through racing's first fifty years the drivers' arms and torsos were very visible, sitting upright in open cockpits, and the spectator could enjoy watching the drivers wrestle with steering wheels, gear levers and weight jackers. It was an impressive sight, essential to the sport's appeal and popularity, but for the past half-century the driver has been all but hidden from view. Today's open wheel race driver appears as nothing more than a barely bobbing helmet and modern in-car cameras make the job of driving the car look like easy with a minimum of fuss or physical effort. All this is far removed from the spectacle that fans enjoyed fifty or one hundred years ago in stark contrast to most other sports which continue to provide the same simple athletic endeavor of a bat striking a ball, or a player catching or throwing a ball. The essence of most sports and the nature of their appeal and spectacle are unchanged but racing has become subsumed by technology so that it's much more clinical, much less spectacular and infinitely safer than in days of yore.  © Racemaker/Knox In addition to totally changing racing's appeal and spectacle these revolutions of the sixties, seventies and eighties pushed speeds through the roof. For years, the sport sold itself on the appeal of ever increasing lap speeds and new track records. But over the past thirty or forty years as the cars were deemed too fast for all types of tracks most sanctioning bodies spent a great deal of time and effort trying to reduce performance and speeds as well as rein in costs. The eternal quest for new track records has been replaced by ongoing efforts to limit or reduce speeds and to make the sport safer by developing more crash-resistant cars and safer tracks bordered by ever-improving barrier systems and yards and yards of run-off room. The focus, more and more, has been on making close, competitive racing rather than encouraging spectacular speeds and performance. NASCAR led the way in establishing this path many decades ago with a longterm commitment to its antique, tube-framed cars strictly defined by an ever tighter rule book. New technology has never been welcome in NASCAR witness the arrival of fuel injection a few years ago half a century after it was adopted by the rest of the motor racing world. NASCAR is about constantly fettling a long-running formula and in that way it's more like other sports than open-wheel or sports car racing.  © Mike Levitt/LAT USA Of course, the greatest legacy from this year's Daytona 500 race week was Kyle Busch's crash in Saturday's Xfinity race. Buch's leg and foot injuries were immediately deemed unacceptable by all and a spate of new SAFER barrier-building has been announced at Daytona, Talladega and Atlanta. Other tracks are sure to follow. But in the bigger picture NASCAR remains fifty years behind the times. Today's much improved seats and safety systems as well as the HANS device were developed in road racing and open-wheel racing. NASCAR adopted more modern thinking about safety long after other forms of racing had made great strides in using technology to good effect but the basic elements of NASCAR's latest Generation 6' Cup car remain rooted in the distant past. A tubular frame is ancient technology, outdated first in the sixties by aluminum monocoque chassis, which were further refined by the use of honeycomb aluminum, then by the appearance in the eighties of carbon composite chassis. Today's carbon composite single-seaters and sports cars are amazingly strong and crash-resistant. Such surroundings surely would have served Kyle Busch well, much better than a tube frame no matter how well-developed it is by NASCAR and its teams. Of course, moving to some form of monocoque or carbon fiber chassis is not even remotely close to being on NASCAR's radar screen. Rather than looking at ways to make a Cup car more modern or technologically relevant or producing more spectacular cars, most of the focus these days seems to be going into searching for ways to make the fan or customer more comfortable, witness Joie Chitwood's discussion about Daytona in 2016 in this space last week. I respect these efforts but I think most people have forgotten about the appeal of the cars themselves. Most sanctioning bodies have spent so many years reducing performance, dumbing the cars down and making them all the same or spec car-like. They've forgotten that racing's original appeal was in spectacular, high-performance cars and larger than life daredevil drivers capable of mastering those mean machines.  © Red Bull F1 For all their faults, F1 and the WEC are trying to adapt, but our domestic sanctioning bodies seem to have fallen into a catatonic state of denial. Nor do the likes of IndyCar or TUSC supply anywhere near enough media space to sell the kind of sponsorship required to pay to design, build, develop and race modern hi-tech F1 or WEC-like cars. As I've written many times, most of us believe the essence has been sucked out of the sport by the bureaucrats and marketing mavens who long ago took over running the sport and sadly we have little faith in these folks restoring the sport to its former glory. Like I said at the beginning, racing is considerably more complicated than most other sports. It requires very smart, savvy management like Bill France Sr. and Bill Jr. provided. I believe a return is necessary to rediscover the sport's original spirit and spectacle, but without the leadership and power base of Bill Sr. or Bill Jr. that mission is exceedingly unlikely of ever happening. |

|

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright ~ All Rights Reserved |