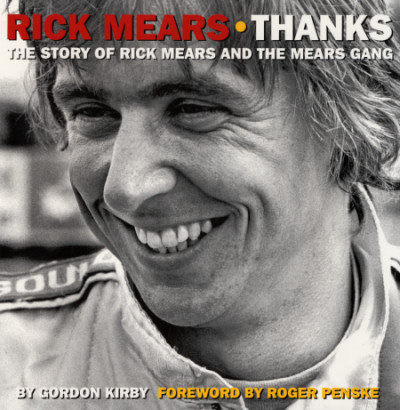

The Way It Is/ 'Rick Mears--Thanks' is available this week

by Gordon Kirby I'm delighted to report that my latest book, 'Rick Mears--Thanks, the story of Rick Mears & the Mears Gang' will debut this week at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Rick and I will sign books at the Speedway this Wednesday, May 21, at 3 pm on 'The Plaza', just behind victory lane. Rick will also join me on Saturday, May 24, for a signing at the Borders on Monument Circle in downtown Indianapolis from 1.30-2.30 pm.

I'm delighted to report that my latest book, 'Rick Mears--Thanks, the story of Rick Mears & the Mears Gang' will debut this week at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Rick and I will sign books at the Speedway this Wednesday, May 21, at 3 pm on 'The Plaza', just behind victory lane. Rick will also join me on Saturday, May 24, for a signing at the Borders on Monument Circle in downtown Indianapolis from 1.30-2.30 pm.

Through the nineteen-eighties and into the early nineties Rick was known as the 'King of the Speedways' and the maestro of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Mears won four Indianapolis 500s and three championships between 1979-1991 before retiring at the end of 1992 following a series of injuries that combined to reduce his ability to operate at the maximum and to enjoy his sport to the best. Mears is one of very few great sportsmen who retired at the height of his career in the immediate aftermath of some of his greatest performances.

Rick grew up racing motorcycles, sprint buggies and off-road cars with his brother Roger. Father Bill was a successful modified stock car racer in the nineteen-forties and fifties and Bill's wife Skip fully supported her husband's and sons' lifelong love of racing. Rick became a Penske driver in 1978 and scored his first win in his third race with the team. Mears went on to win the 1979 Indy 500 and establish an enduring relationship with Penske that lasted through and beyond his retirement from driving at the end of 1992. Ultimately, he won four Indy 500s (equalling the record set by A.J. Foyt and Al Unser), three championships and twenty-nine Indy car races, and was admired and respected not only as a superb driver and racer but as a rare gentleman on and off the track.

I've endeavored to tell the whole story of 'Rocket Rick' and the Mears Gang's journey from dirt tracks to superspeedways. The book also shows us how any sportsman or woman should behave as a professional and as a human being. When Rick stepped out of the cockpit he enjoyed a superlative reputation as one of the cleanest, most sportsmanlike race car drivers the world has ever known.

"He was very polished," says Mario Andretti in the book's Prologue. "He was probably one of the most correct drivers out there to race against. I always had the greatest respect for Rick Mears."

© Jim Schweiker Archive

In his new role as team leader, Rick was deeply aware that he had to step up both as a test driver and a qualifier. During 1981, he had already begun to contribute more to the Penske team's test program and was comfortably confident that he could provide the leadership required to push the test program forward.

"I felt like I helped the engineers as far as relaying to them good information as far as feeling the car, what the car is doing, how it reacted to the changes, so they could build a better picture. Because they didn't get to feel the car, I had to explain a picture for them as clearly as I could so they could understand more of what they needed to do to fix the car. Trying to draw that picture as clear as possible was part of the fun. Later, after I retired, I learned a lot more respect for the engineers' efforts in trying to build a better mousetrap without being able to feel the car.

"I always enjoyed competing with the engineers," Rick adds. "I always wanted to work very close with the engineers and understand what was going on. I had the advantage of being able to feel the car, which they didn't. I would compete with them to try to see if I could put my finger on the problem, whether it was spring, aero, shock, toe, camber, whatever, before they could, which in turn helped speed-up the process for the whole program."

Rick was a little less confident in his ability to master the art of qualifying. "It took me several years to learn how to qualify," he admits. "I didn't really start qualifying until Bobby retired. We had qualified on the pole a few times, but I was still learning how to qualify. I was very fortunate with Roger because he allowed me time to learn. He didn't expect me to do it right off the bat. He never put pressure on me. He just let me take it at my own pace. Then, after Bobby retired, I was the senior driver on the team and that put a little more pressure on me to qualify well. Now it was up to me. Before that, Roger would just say, 'Just get in the show and get some miles.' But now I had to qualify.

"In the early years," Rick continues, "I'd go out and qualify and I'd see these other guys beat me, and in the race they'd be three or four mph slower and I'd be running the same speed I qualified at. I thought, 'What's wrong with those guys? Why can't they still do it in the race?' Then I realized that I wasn't qualifying to the maximum. I was qualifying well because we had good cars and good equipment, but I was still leaving something on the table.

"So you just keep pushing. I found out I could qualify at one speed but I couldn't race that hard all day because I couldn't hold my breath that long! I discovered that some days I wasn't holding my breath when I was qualifying. It's something you have to work yourself into and learn, and you also have to learn how to set the car up to qualify versus the race. Before that, I was always trying to make the car the way I wanted it for the race. But as time went on you learn how to free it up more for qualifying, how to run on the limit more, and run more on the right rear tire instead of the right front."

Rick deliberately used his natural inclination to be as silky smooth as possible to keep pushing the limit. "I've always tried to be smooth and I think that helped on the faster tracks, on the speedways. By not being erratic you can run closer to the limit more consistently without stepping over it. If you're erratic, you've got to give yourself more of a cushion, so your average overall isn't going to be as quick. If you're smooth and run closer to the limit, lap after lap, it adds up. I think that was more my natural style.

© Bob Tronolone

"Plus, different cars over the years would tell you how much you had left and what type of step you would take the next time through the corner. The cars talk to you and you have to listen to them. If you don't listen to them, you're going to step over the limit."

Incredibly, Rick did not spin a car during his first five years with Penske. "It was making me nervous that I hadn't spun one because I saw other guys doing it, and I thought, 'What am I leaving on the table?' I knew I was going to spin sometime. Obviously, I didn't want it to happen. Back then, if you spun, they frowned on it. Today, they frown on it if you don't spin once in a while. That's the difference in the competition level today and the mindset, which is if you don't do something wrong once in a while you must not be trying hard enough. But back then, it was the other way around.

"So I didn't want to spin and when I did finally spin it, I realized that I had been very, very close a lot of times, a lot of times! I was just fortunate it hadn't happened. That was when I realized I wasn't leaving a lot on the table.

"That's what this sport is all about and always has been," he adds. "It's a continuous learning curve, no matter how long you've been doing it. If you quit learning, that's when it's time to get out."

And this from Chapter 18 after Rick had taken his fourth Indy 500 pole in 1988:

Rick's pole was his fourth at Indianapolis and the eighth time he was on the front row in eleven starts. It was also his fourth new qualifying record and by now almost everyone recognized him as the King of the Speedway. Rick is unequivocal in calling the Indy 500's four-lap qualifying run the toughest test in racing.

"Qualifying at Indy is the toughest thing of all," he declares. "To me, the race is a piece of cake compared to qualifying. You've got 500 miles to work on the car and get it sorted, but to get the most of it for four laps and to get all four laps exactly right at Indy is the big challenge. It's all about the fine-tuning of watching the weather and the cloud cover, and the logging of what turn one felt like on the first lap so when you came around again you could log how the track had changed in turn two and turn three and turn four so you could make the corrections in turn one to get the most out of it. And then you had to log how it felt there to get the most out of it in the next turn, and so on, all the way around the lap for four laps.

"You have to do that every corner, every lap," he adds. "You're continuously logging what the car is doing and changing your pattern and the sway bars to get the most out of it at the next corner you come to."

Rick is quietly proud that he was capable of keeping all these things in mind while driving the car on the ragged edge through the fastest corners in the sport. "It's almost like every time you go through the corner is the first time," Rick observes. "Because of what you felt on the last corner you are going to make a change in your pattern in the next corner and hope it's right because you didn't do it the time before. To do that for all four laps as the tires go off and you were also keeping track of how much the tires change from corner to corner, that was tough! But it's also one of the most satisfying things in racing because it's so tough."

© Bob Tronolone

"The best part about sitting on the pole anywhere, not just at Indy, was I felt like I had paid my guys back for all the hard work they'd put in to put that car under me," he reflects. "It was like a payback to them for all their hard work. You loved coming down pitlane and seeing the smiles on their faces and seeing them so happy. And the sponsors too and everybody else, besides yourself feeling good because you're competitive. You know you're in the hunt. So it's really satisfying in all respects."

Penske Cars' longtime managing director Nick Goozee began his career in racing with the Brabham F1 team in the mid-sixties so Goozee has had up-close experiences with many of the greats of both F1 and Indy car racing from Jack Brabham and Dan Gurney to Mario Andretti and Bobby Unser. In Goozee's opinion, Rick's pole qualifying ability was on a rarified plane above any other driver.

"Watching him prepare for one of his pole positions at Indianapolis, he was quite unlike other driver," Goozee says. "He almost knew in advance what he was going to be able to achieve. There were never any histrionics with Rick. We had lots of other drivers and with all of them, there was always an issue. Either the tension was getting to them, or there was some reason why something wasn't happening which they felt they needed.

"Rick never, ever accused the equipment of being his problem," Goozee continues. "He knew that if he had a bad car, the only person who was going to make the car go quicker was him. There was going to come a point where he was going to have to step-up. Other drivers made a decision that the car wasn't capable of achieving the speeds the driver wanted and they got it to where they were comfortable, and that was it. They settled for that. But Rick never did that. He always took the car way beyond its limits. Mario did it occasionally. He was quite capable of doing that, too.

"But there was sort of a quietness about Rick. He seemed to enter a zone whereby he was still communicative. He didn't have to go and hide away in a motorhome, or lay down and go into a trance-like state. He would go and sit on the guardrail and chat to a few friends, but while he was talking he was already working out what he had to do. He was preparing himself. A part of him was set aside carrying on business, while the other part of him was just laughing and socializing and making light of the situation."

Goozee recalls the electric atmosphere that used to accompany Rick onto the track when he went out to qualify. "When the time came, he would climb into the car and sit down and get strapped in, and then he'd go quiet," Goozee remarks. "It was odd. You almost got goose bumps when he went out because you knew something was going to happen. You put most drivers in the car and off they go and it's quite interesting and exciting, and there have certainly been occasions when people put cars on pole position when it wasn't expected. But with Rick you just knew that something was going to happen. It was like everybody in the stadium held their breath. When Rick went out, they just watched. There was a reverance with him at his peak that I don't think anybody else got.

"I didn't see it with any of our other drivers. Mario was the only one. There was something uniquely special about Mario, but the uniqueness of Rick was different. Mario was the consummate racing driver/businessman who had his feet in lots of pies and once he stepped out of the car he carried on with his business. Mario got in the car and did what he did and was passionate about his racing.

"But with Rick there was this remarkable confidence in what he could do," Goozee concludes. "You knew if Rick qualified first, fifth, fifteenth, or twentieth, that was the maximum that car could do. He said, 'This is the equipment I've got. This is what I've got to deal with. This is what I've got to race this weekend and we'll find a way of doing it better next weekend.'."

A curveball was thrown at everyone in the starting field for that year's Indy 500 when heavy thunderstorms in the days before the race washed all the rubber off the track. It would take a different set-up than at any time all month for anyone to get the best out of their cars on raceday and Rick and his crew were among those who guessed wrong. His car was wildly tail-happy in the opening laps while teammate Sullivan hit the right combination and was able to pass Rick right away and take control of the race.

Rick fell back steadily, his car's handling getting no better until the race's first and second pitstops at roughly one hundred and two hundred miles. In consultation with Rick, his crew made adjustments to tire staggers and wing angles and even changed the type of wheels Rick was using from the the theoretically aerodynamically smoother, flush-faced wheels used in qualifying to more conventional, deep-dish wheels. At one point Rick fell almost two laps behind, but by half-distance he was charging his way back into contention.

As more and more rubber went down the track continued to change and Sullivan's car started to understeer or push badly. His problem was aggravated by a broken front wing adjuster and all of a sudden he found himself caught and passed, not only by Rick but also by Al Unser in the team's third car. A few laps later, Sullivan hit the wall in turn two, bringing a sad end to a day which had started so well.

Meanwhile, Rick's car was now working perfectly and he ran away with the second half of the 500. The race finished under a yellow after Michael Andretti's car lost a piece of bodywork on the frontstretch and Emerson Fittipaldi's Patrick March-Chevy was the only other car to finish on the lead lap with Rick. Al Unser was a lap down in third after problems of his own with the front wing adjuster and a foul-up with the pace car.

"We went two laps down and came back and won the damn thing!" grins Peter Parrott who was Rick's crew chief in those days. "To be that far down and come back and win the race was a great win for Rick. That was very satisfying. We were struggling and everybody on the team, the engineers and everybody worked bloody hard to get the car back to the way he liked it. That's the thing I liked about that race over 500 miles. If it falls for you and you have a little bit of luck, you can come back with the yellows, or at least you could in those days."

Rick explains the benefits he gained in qualifying and the problems created in the race by running the flush-faced wheels which were new that year. "We always fought a little mid-turn understeer," he comments. "If we got the car where if it wasn't too loose going in, or too loose coming off the corner, it always had a little understeer right in the middle of the turn, and if I got the mid-turn understeer out, I was too loose going in. But when we tried the flush wheels, it brought the car right in the middle of the corner without affecting my entry or exit. That was where those wheels really helped. We thought it was great because you also fight understeer when you're in traffic so we thought those wheels would be good for traffic.

"Then when the race started the car went really loose. Where it was loose was right where I knew we could fix it if we took those wheels off. I knew that if we got rid of the looseness in the middle of the corner by changing the wings, I would be pushing on entry and exit. I knew we weren't going to be able to fix it and keep on running the flush wheels. I think we made one stop and tried to adjust it and that was when I figured out that we weren't going to fix it with the wings. We were going to have to change the wheels because what the wheels added is what I needed to take away. So I radioed in and told them I really wanted to change the wheels."

Ace fabricator and right rear tire changer Jerry Breon also worked as Rick's tire man and at Rick's suggestion he leaped into action. "Breon probably about dropped because he had to change all the wheels and tires," Rick half-jokes. "But he started hustling to get the tires and wheels changed and as soon as we bolted the other wheels on the car was great. The guys made all the right calls in the pits and from that point on it was just a matter of fine-tuning and following the conditions of the track as the race went on and staying ahead of it. The car was really good and it was just a matter of running all day and not making any mistakes. Once we got back on the lead lap we had everyone covered."

Peter Parrott rates Rick as the finest oval racer he's ever seen. "I think Rick was a heads-up driver and he was engineering-savvy, too," Parrott observes. "He took a lot of interest in the car and the setups, which a lot of people don't these days and don't really understand. But Rick did. He knew when he went out what he could do, especially on ovals where he was very, very strong, as we all know. His weakest point, I would think, was on road courses, and I think he would acknowledge that.

"But on the ovals, he was the master. He knew exactly what he needed to have and what the car could do, and he could push the car to the limit. He was very comfortable with that. You knew when he went out on the track that if the car was right he would put a quick lap in, and it was effortless for him. At least, it seemed effortless. We just knew that when the car was right, Rick was always a force and we could win the race.

"On most tracks, especially the big ones, he used to run the car pretty loose," Parrott adds. "He knew that the only way to be quick was to be loose. Unlike Al Sr., who was older at the time and would always have a car that was pushing because it was more controllable, Rick would have it on four-wheel drifts. He didn't seem to mind at all. Rick had complete control. He knew exactly what the car could do and he knew what he wanted. When you're working with a guy like that where the small changes will make the difference, it was a sheer joy."

Adds Ilmor engine designer Mario Illien: "Rick was incredibly precise in what he was doing and saying. He would get in the car, do five or six laps and give the guys a catalogue of things to change on the car. Then he'd go out and run faster and come back with a new catalogue of things to change. Every time he went out he would make improvements and go faster. He had an incredible feel for the car and could make changes in the car to improve the car. He was very technical. He had a very, very good understanding and feel for what was going on. He could adapt to changing conditions. Rick was a master of all those things."

It was a great pleasure to write about such a great driver and fine man. I hope you enjoy the book.

*'Rick Mears--Thanks' is published by CMG Publishing who produce the Autocourse, Rallycourse & Motocourse annuals. The book is available at Borders and most good book stores for US$39.95. You can also order the book from www.autocourse.com. ISBN: 978-1-905334-30-8

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright 2008 ~ All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2008 ~ All Rights Reserved

Top of Page