The tale of Tommy Milton and Jimmy Murphy, two of America's greatest drivers

by Gordon Kirbyillustrated by LAT

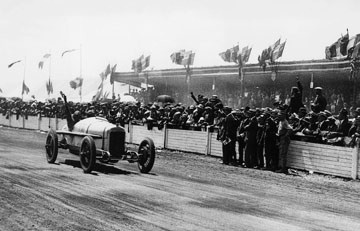

Milton and Murphy also set new land speed records on Daytona Beach in the spring of 1920, becoming the first men to exceed 150 mph, while Murphy scored an historic victory in the 1921 French Grand Prix. Driving for the Duesenberg team, Murphy scored the first all-American win in Grand Prix racing, a feat that would not be duplicated until Dan Gurney won the 1967 Belgian GP aboard his own Eagle-Weslake F1 car.

Murphy was a gentleman and fan favorite who has gone down in history as the 'King of the Boards'. Tragically, he was killed at the height of his career in a dirt track race at Syracuse, New York in September, 1924. Milton continued to race until the end of 1927, retiring just before his thirty-fourth birthday. He worked in a variety of businesses and was chief steward at Indianapolis for many years. Suffering in his later years from burns received in a 1919 accident, Milton died from self-inflicted gunshot wounds in 1962 at 68 years of age.

Like most of the great drivers from that era, Milton and Murphy were top-flight mechanics and self-taught engineers. Milton arrived a few years before Murphy, starting his career as a driver with J. Alex Sloan's state fair automobile barnstorming act before making the move into AAA racing in 1916. Blind in one eye from birth, Milton drove for Fred and Augie Duesenberg's team and scored his first win in 1917 on the concrete oval at Providence, Rhode Island.

Murphy was raised by his uncle and aunt on a ranch in Los Angeles after his father died in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Murphy started his career as a riding mechanic with the Duesenberg team and won in his debut sitting beside Eddie O'Donnell in a 300-mile road race in Corona, sixty miles east of downtown LA. He also finished third in that year's Vanderbilt Cup race in Santa Monica partnering wealthy driver Bill Weightman. By 1919 Murphy had graduated to the driver's seat and he scored his first win in February of 1920 in the debut race at the sparkling new Los Angeles Speedway board track in Beverly Hills. The hometown boy became an instant national hero.

In April of that year Milton and Murphy were at Daytona Beach to run Milton's 'Beach car', a twin-engined Duesenberg designed specifically by Milton to break the land speed record. While Milton was busy at some demonstration runs in nearby Havana with other early racing superstars Barney Oldfield and Ralph de Palma, Murphy was asked by Fred Duesenberg to test drive the 'Beach car'. Murphy's test runs weren't officially timed, but he went five mph faster than de Palma's record from 1919, running 154 mph.

This episode exacerbated the rivalry between Milton and Murphy and also resulted in Milton's departure from the Duesenberg team. Disgusted that Duesenberg had encouraged Murphy to run so fast in his test run, Milton went his own way at the end of the 1920 season.

Meanwhile, the 1920 Indy 500 was won by Gaston Chevrolet's Monroe/Frontenac after Ralph de Palma's dominant Ballot ran out of fuel. Chevrolet was the youngest of the three Chevrolet brothers who had sold their brand to General Motors founder Will Durant a few years earlier and were now building their own cars called Monroes or Frontenacs. Unlike most other races, the Duesenberg team rarely seemed properly prepared for Indianapolis and Milton and Murphy came home third and fourth in the 500 after qualfying eleventh and fifiteenth. But in most races that year the Duesenbergs usually were the cars to beat.

Only five races were listed on the AAA championship schedule in 1920 and the season-closer was in November at the 1.25-mile Beverly Hills board track where Murphy had won in February. By this time Milton had quit the Duesenberg team and his place was taken by Roscoe Sarles who won the race. Murphy finished second while late in the race Indy winner Chevrolet was involved in a terrible accident with another Duesenberg driven by Eddie O'Donnell. Chevrolet, O'Donnell and the latter's riding mechanic Lyall Jolls were killed in the accident and the result was that Chevrolet was a posthumous AAA champion, thanks largely to his win at Indianapolis.

Seven years later, mind you, the AAA revised the historic record, adding five races to the 1920 series and declaring Milton that year's champion. The AAA's revised rankings made Murphy the championship runner-up and dropped Chevrolet to third as well as creating an arcane historical dispute that rages to this day.

Meanwhile, Milton joined the Frontenac team for the 1921 season, taking over the deceased Chevrolet's seat. De Palma again dominated the Indy 500 aboard his French-built Ballot but blew his engine, allowing Milton to score a comfortable victory. Murphy crashed out of the 500 but the following month the Duesenberg team sailed to France to compete in the French Grand Prix. Because of WWI, the world's oldest and only Grand Prix race had not been run since 1914 and the Duesenberg brothers took a team of four cars, proudly painted in America's white and blue international racing colors, to the French Grand Prix's revival in 1921.

Murphy's teammates in France were Joe Boyer, a wealthy but excellent driver who would win the 1924 Indy 500, veteran French driver Albert Guyot, and wealthy Frenchman Louis Inghibert who crashed in practice and was replaced by Andre Dubonnet. The favorites for the 30-lap race over the 10.7-mile Le Mans circuit were France's own Ballot team with Jules Goux, Jean Chassagne and Ralph De Palma driving. But the Duesenbergs ran with the Ballots in the race and beat the French cars thanks primarily to better brakes. The Duesies enjoyed hydraulic brakes and were much quicker into the corners than the mechanically-braked Ballots.

Joe Boyer led but blew his engine halfway through the race while Murphy turned the race's fastest lap in 7 minutes 43 seconds, averaging just over 80 mph, and beat de Palma by fifteen minutes with Goux finishing third, Dubonnet taking fourth and Guyot sixth. Suddenly, Murphy was an international racing hero.

Back home, Murphy and the Duesenberg team missed three AAA races, allowing Indy winner Milton to build up an insurmountable championship lead. Milton went on to win that year's AAA title from Roscoe Sarles and Eddie Hearne with Murphy finishing fourth in points. Milton won the 1921 title aboard a variety of cars, driving his own Durant with both Duesenberg and Miller engines as well as a factory Frontenac.

Milton's Miller-powered Durant was his primary mount for most of 1921 and the early part of 1922. The Miller engine was fitted with new cylinder heads Milton had pirated from Duesenberg and Milton called the car, 'the spotted-assed ape'. Milton's results with the car prompted Murphy to buy a Miller engine and install it in his Duesenberg, creating the Murphy Special. In this car Murphy dominated that year's Indy 500, qualifying on the pole and leading most of the race to win at record speed.

Murphy and Milton battled for the 1922 title with Murphy winning seven races and Milton four. In the end, Murphy easily won the championship with Milton second ahead of Duesenberg's new lead driver Harry Hartz. In the middle of the year the AAA banned Milton's Durant-Miller because a Durant dealer had advertised that the cars he was selling had the same engine as Milton's car!

For the 1923 season both Milton and Murphy were driving Harry Miller's cars, chassis and engine both. Milton's cars were sponsored by the Stutz car company and Murphy's by Durant. Milton was on the pole and led most of the way to win at Indianapolis with Murphy finishing third, but neither enjoyed very good seasons. Murphy won two early-season races but his challenge for the championship was blunted by another foray to Europe in the fall of '23, this time to compete in the Italian GP at Monza. In the end Murphy was beaten to that year's AAA title by Eddie Hearn while Milton failed to win another race after Indy and finished fifth in the championship.

The Italian GP came to life in 1922 as the world's second Grand Prix race when the new Monza circuit was opened. Harry Miller entered three of his cars for the 1923 Italian race. Murphy drove one of the cars with European drivers Count Zborowski and Martin de Alzaga aboard the other two, but Fiat had developed the first supercharged racing engine that year and not even Murphy could keep up with the Fiats. He also had brake trouble in the race but was able to make it home in third, five minutes behind two of the Fiats driven by Carlo Salamano and Felice Nazzaro.

Fiat's introduction of supercharging prompted Duesenberg to develop a supercharged engine for 1924. Miller continued for another year with normally-aspirated engines and although Murphy qualified on the pole at Indianapolis and lead a quarter of the race he was overwhelmed by Joe Boyer in one of the superchagred Duesenbergs. Veteran Earl Cooper finished second as Murphy fell to third because of tire troubles.

But after Indy, Murphy went on a tear, winning three races in a row on the boards and taking control of the year's championship. A single dirt track race at Syracuse, New York had been added to the AAA's championship schedule for 1924 and despite his distate for dirt tracks Murphy showed up to compete. He was running a strong second late in the race when a shock absorber appears to have failed, throwing his car into the wooden barriers. One of these crushed Murphy's chest, killing him almost instantly. So dominant was Murphy that year that he still won the championship even though there were still three races to be run after his death.

For his part, Milton continued to race for three more years through 1927. He won the season-opener in 1925 and finished second to Peter de Paolo in that year's championship but wasn't a serious factor in the following two years before retiring.

In his excellent book, 'King of the Boards', Gary Doyle presents convincing anecdotal and statistical evidence that Murphy deserved the title ahead of Lockhart, Milton, de Palma and de Paolo. This was the height of the board track era which was beginning to collapse by the time Lockhart arrived on the scene in 1926 and was essentially over by 1928. The Altoona, Pennsylvania board track survived into 1931 but the track's closure at the end of that year marked the end of the great board track era.

For those interested in learning more about this halcyon period in American racing history I highly recommend Doyle's book. Also well worth reading are Griff Borgeson's 'The Golden Age of the American Racing Car', Mark Dees' 'The Miller Dynasty', and Dick Wallen's 'Board Track: Guts, Gold and Glory'. A search of your local library through back copies of Automobile Quarterly and for Pete De Paolo's 1930s book, 'Wallbanger', will also prove rewarding. I'm sure you'll enjoy the journey.

Auto Racing ~ Gordon Kirby

Copyright 2006 ~ All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2006 ~ All Rights Reserved

Top of Page